“The ancient Egyptians had an ambivalent relationship with hippopotami. Although the animals were endowed with positive qualities, they were also feared as dangerous. Hippos are indeed unpredictable and powerful animals that—when feeling threatened—will become extremely aggressive; today hippopotami kill more people in Africa than any other large animal. A hippopotamus can outrun a human over a short distance, and they often upend boats and maul passengers. Ancient Egyptians were attacked by hippos, but evidence that people also survived can be found in an ancient Egyptian medical recipe for wounds inflicted by the bites of a hippo. Hippopotami are herbivores and usually graze during the night, when they can decimate a farmer’s field with their enormous appetite. This was already an issue in ancient Egypt; an inscription on a papyrus refers to such a devastated harvest: “the worm took half and the hippopotamus ate the rest.”

“From the New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.) on, the hippopotamus was connected to the god Seth, and in later times Seth was seen as an evil character. The god Horus was the mythological prototype of the king, and in the myth of Horus and Seth, Horus defeats Seth and ascends the throne they had battled over. Ritual enactments of this story were recorded in about 100 B.C. on the walls of the temple of Edfu. These scenes show Horus, who is often depicted together with the king, harpooning Seth in the shape of a hippopotamus.

“But the ancient Egyptians also recognized hippopotami as positive creatures. Hippos lived in the Nile River, the source of life, so they, too, were associated with life. They often submerge in water for several minutes, surface to breathe, then sink again; this behavior of disappearing and reappearing was associated with regeneration and rebirth. Sometimes only the back of a hippo is visible, which resembles land surrounded by water, an image the Egyptians might have linked with the primeval mound and the beginning of creation. In one Egyptian creation myth, there is the primeval water out of which the primeval mound emerges and on which the sun rises for the first time. In another version of this story, the sun god appears for the first time on top of a lotus flower that arises from the primeval water. The primeval water, the primeval mound, and the lotus flower were thus all connected with creation and life. Another intriguing behavior of hippos is that they roar in the morning at sunrise and in the evening at sunset. The Egyptians possibly interpreted this behavior as a greeting and farewell to the sun. And the sun’s travel was seen as an eternal cycle of rebirth that the deceased hoped to join. Hippopotami were thus associated with life, regeneration, and rebirth. Depictions of them, such as statuettes (see below) or small seal amulets (10.130.771), could magically transfer these qualities to their owners.

“The ancient Egyptians also observed that female hippos fiercely protect their young. The dangerous yet protective aspect of hippos was probably one of the reasons Taweret (26.7.1193), a goddess who protects mothers and children, was depicted as part hippo. The fact that female hippos usually bear only one young, as do humans, is perhaps another reason. Similar hippo goddesses are known under the names of Ipet and Reret.

“Another positive hippo creature was the goddess Hedjet, who is depicted in full hippopotamus shape and is known from a festival. Her name might mean “The White One,” though this translation has been debated. In the past, her ceremony has often been connected with the royal hippo-hunting ritual. However, they are not necessarily linked, especially since the name Hedjet never occurs in hippo hunting scenes, and the hippo never has a negative connotation in the scenes where it is called Hedjet. Egyptologists have often distinguished between a good female white hippo and an evil male red hippo, but this distinction is problematic as there exist representations of red female hippos (23.2.30), and female hippos are not always seen as positive. An example of a negative connotation of a part-hippo female creature is Ammut (the Devourer) in final judgment scenes: if it is determined that the deceased had failed to live a moral and just life, this creature will devour his or her heart, and the person will cease to exist.

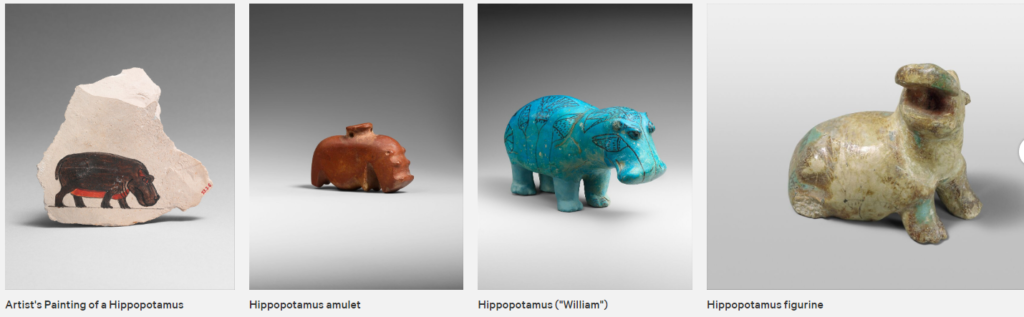

Many different types of hippopotamus representations occurred throughout ancient Egypt (23.2.30; 43.8a,b; 23.3.6; 1997.375; 20.2.25), but the most famous are doubtless the wonderful faience hippopotami (17.9.1; 26.7.898; 08.200.37; 32.1.230; 66.99.13) that are known mainly as grave goods and date to the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1650 B.C.) and Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1650–1550 B.C.). Nearly one hundred such faience hippos are preserved in collections worldwide. The exact archaeological context for the vast majority of these figurines is unfortunately unknown. One of the Metropolitan Museum’s hippos is an invaluable exception, as it was recorded that it was found within the wrappings of the mummy of Reniseneb (26.7.898). The bodies of most faience hippos are densely decorated with river plants. Foremost are depictions of closed and open lotus flowers and lotus leaves (17.9.1). Other plants such as the pondweed are common, and many figurines also incorporate the depictions of Nile creatures such as frogs (32.1.230), butterflies, birds (66.99.13), and occasionally dragonflies (08.200.37). Intriguing circular ornaments also appear (26.7.898; 66.99.13); these could be stylized representations of flowers seen from above, but the suggestion has also been made that they are depictions of floats that were used in the hippo hunt. The latter explanation is not fully satisfactory though as such floats are usually shown in a triangular or elongated shape. The decoration of the faience hippos represents the animals’ natural habitat, but in addition these plants and animals also had many positive associations with growth and life. The lotus flower was an especially popular symbol of regeneration and rebirth, since it opens in the morning when the sun appears and closes in the evening. It was linked to the eternal cycle of the death and rebirth of the sun god. The deceased hoped to join the travel of the sun god, in order to be reborn together with him every morning. And, as mentioned above, the lotus flower was also connected to the beginning of creation and thus to life.

“The faience hippos were linked to the themes of life, regeneration, and rebirth through many different layers that included the behavior of the animals themselves as well as the decoration of these statuettes. When placed in tombs, they were meant to supply the deceased with regenerative power and to guarantee his or her rebirth. Since the ancient Egyptians also feared these animals and believed that depictions of them could magically come alive, the legs of many such statuettes were probably broken off deliberately, thus eliminating the animal’s destructive potential. The faience hippos have been interpreted in many different ways. Besides the interpretation supported here, that they ensured regeneration and rebirth, it has also been suggested, for example, that they function as icons of the hippo hunt. The latter is partially due to the fact that cross bands above their backs have been construed as depictions of ropes. It is possible that rather than referring to the hippo hunt, they are meant to control the animals’ dangerous aspect. As with the broken legs, these bands might represent the ancient Egyptians’ ambivalent relationship to the hippo.

Stünkel, Isabel. “Hippopotami in Ancient Egypt.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hipi/hd_hipi.htm (November 2017)

Hippopotamus (“William”)

Figure of a Hippopotamus. Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Senwosret I to Senwosret II (ca. 1961–1878 B.C.). From Egypt, Middle Egypt, Meir, Tomb of Senbi. Faience; L. 20 cm (7 7/8 in.); W. 7.5 cm (2 15/16 in.); H. 11.2 cm (4 7/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

“This statuette of a hippopotamus (popularly called “William”) was molded in faience, a ceramic material made of ground quartz. Beneath the blue glaze, the body was painted with lotuses. These river plants depict the marshes in which the animal lived, but at the same time their flowers also symbolize regeneration and rebirth as they close every night and open again in the morning.

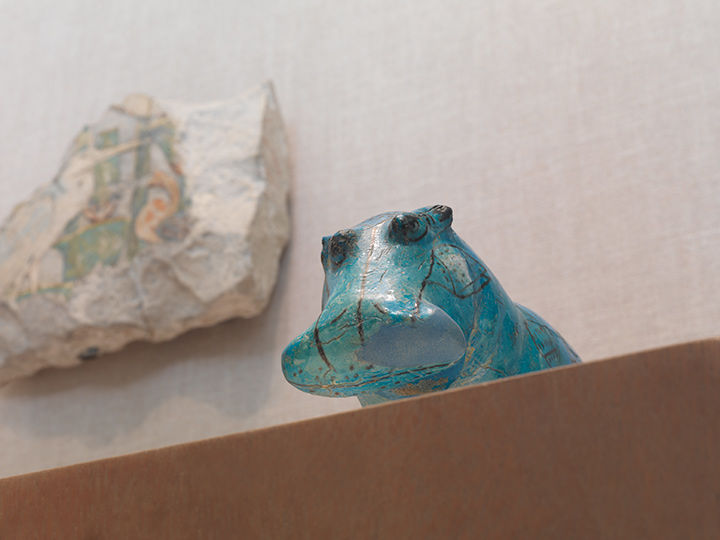

“The seemingly benign appearance that this figurine presents is deceptive. To the ancient Egyptians, the hippopotamus was one of the most dangerous animals in their world. The huge creatures were a hazard for small fishing boats and other rivercraft. The beast might also be encountered on the waterways in the journey to the afterlife. As such, the hippopotamus was a force of nature that needed to be propitiated and controlled, both in this life and the next. This example was one of a pair found in a shaft associated with the tomb chapel of the steward Senbi II at Meir, an Upper Egyptian site about thirty miles south of modern Asyut. Three of its legs have been restored because they were probably purposely broken to prevent the creature from harming the deceased. The hippo was part of Senbi’s burial equipment, which included a canopic box (also in the Metropolitan Museum), a coffin, and numerous models of boats and food production.

“The hippo’s modern nickname first appeared in 1931 in a story that was published in the British humor magazine Punch. It reports about a family that consults a color print of the Met’s hippo—which it calls “William”—as an oracle. The Met republished the story the same year in the Museum’s Bulletin, and the name William caught on!” The Met

William the Hippo in gallery 111 in September, 2015. Photograph by Mark Morosse

Image Credit: The Met

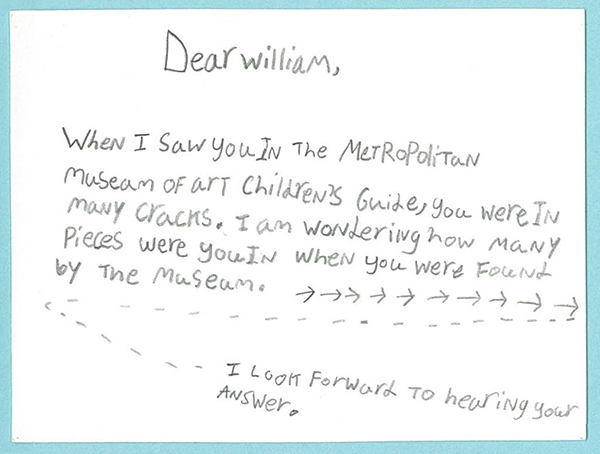

“Year after year, letters from kids around the world flood into the Met. Some curious kids send us their most pressing questions, like what we would save in an emergency, or how many works of art do we have in the entire Museum. Others send in their completed Kids Q&A guides, or get inspired by E. L. Konigsburg’s book The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler and tell us where they would hide if they ran away to the Met.

“Even our artworks receive letters, like this one from a kid named Eli addressed to the unofficial Museum mascot, William the Hippo:

Eli’s letter to William the Hippo. Image courtesy of the author

“Thanks for your question, Eli! Even though William can’t write back, we do have a team that reads all of the letters that come our way, and they do their best to respond to as many as they can. Associate Curator Isabel Stünkel and Conservator Ann Heywood tackled this question:

William came to the Museum as one piece. However, he was missing three of his legs, which were purposefully broken off in ancient time. Hippopotamus figurines such as this one symbolized life and rebirth, but the hippopotamus was also known as a very dangerous animal. The ancient Egyptians believed that depictions of living creatures could magically come alive, so his legs were broken to protect its owner. Only William’s front, proper left leg is ancient, the other three are modern reconstructions. The cracks you see are only in his glazed surface and don’t go all the way through. They probably happened when this statuette was fired and then cooled. Since the body and the glaze possibly cooled down at different speeds, the glaze cracked! These cracks were probably not very visible at first, but over time (he is nearly four thousand years old!) they became more visible. This is because the cracks weathered more

Sena, Aliza. “A #MetKids Question for William the Hippo.” The Met, 24 Sept. 2015, www.metmuseum.org/blogs/metkids/2015/william-hippo-letter. Accessed 16 Jan. 2023.

Wiliam the Hippo at the Metropolitan Museum of At

“In spite of his popularity, there is much we don’t know about William the hippo. What methods were employed nearly 4,000 years ago to form, glaze, and fire this lovable Egyptian faience creature, who came to The Met in 1917? In honor of his 100th anniversary at the Museum, William paid a visit to the Department of Objects Conservation. Although we’ve examined some wonderful ancient Egyptian faience objects, we’d only admired William through a glass case, so it was exciting to have him in the lab in person!

William is fashioned from Egyptian faience, a ceramic material with a siliceous body and a translucent glaze, most commonly turquoise blue or green in color. Made primarily of silica sourced from quartz pebbles and sand, faience contains several other components, including water-soluble alkaline salts, such as the carbonates of sodium, and lime. The Egyptians used various colorants for the glazes, including copper minerals, which produced the most commonly seen turquoise. These dry ingredients, ground into a fine powder, were then mixed with water to create a thick paste.

“Once wet, the differences between faience and clay are immediately apparent. Wet faience paste displays an interesting quality known as thixotropy. When a force known as a “shear” force—a side-to-side movement, for example—is applied to the paste, it becomes more fluid and slumps. Faience paste, unlike clay, is non-plastic. It cracks when folded, and it cannot support its own weight. Due to these limitations, there are fewer methods for shaping faience than for clay. The paste can be modeled by hand or pressed into fired-clay molds; wet faience can also be worked into a slab by shaking and patting; or the paste can be formed around a combustible core.

Image Credit:The Met

Faience replication experiment: paste during the drying process (left), and after firing (right)

“In ancient times, faience was glazed using three different techniques: efflorescence, cementation, and direct application. The efflorescence technique can be described as “self-glazing,” because the colorant is added to the wet paste and migrates to the surface along with the alkaline salts as the faience dries, forming a salty crust. During firing, this layer reacts with the finely ground silica and lime to form a glaze.

Cementation is another self-glazing technique. Here, the unglazed faience core is buried in a “glazing powder” before being placed in the furnace. After firing, the crusty powder is broken away to reveal a glazed surface.

Finally, the direct-application technique more closely resembles typical ceramic methods of applying liquid glaze to a fully formed object. Once dry, the pieces must be fired in a kiln (between 870º C and 920º C) to reveal their brilliant color.[1]

[[1] Charles Kiefer and A. Allibert, “Pharonic Blue Ceramics: The Process of Self-glazing,” Archaeology 24 no. 2 (1971): 107–17; and Pamela B. Vandiver, “Technological Change in Egyptian Faience,” in Archaeological Ceramics, ed. Jacqueline S. Olin and Alan D. Franklin (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1982), 167–79.]

“To learn more about the specific materials and methods used to make William, who was found at Meir in Middle Egypt and dates to the early Twelfth Dynasty (ca. 1961–1878 B.C.), we began by performing visual observation with a stereomicroscope. Conservators use this instrument to get a closer look at surface details, which can help them better understand how an object was made and its state of preservation.

Serotta, Anna. Getting to Know “William”—Inside and Out. 24 Oct. 2017, www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2017/william-hippo-conservation. Accessed 16 Jan. 2023.