Baldwin, James. Heroes of the Olden Time: A Story of the Golden Age, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons 1927.

THE FORE WORD.

You have heard of Homer, and of the two wonderful poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, which bear his name. No one knows whether these poems were composed by Homer, or whether they are the work of many different poets. And, in fact, it matters very little about their authorship. Everybody agrees that they are the grandest poems ever sung or written or read in this world; and yet, how few persons, comparatively, have read them, or know any thing about them except at second-hand! Homer commences his story, not at the beginning, but “in the midst of things;” hence, when one starts out to read the Iliad without having made some special preparation beforehand, he finds it hard to understand, and is tempted, in despair, to stop at the end of the first book. Many people are, therefore, content to admire the great masterpiece of poetry and story-telling simply because others admire it, and not because they have any personal acquaintance with it.

Now, it is not my purpose to give you a “simplified version” of the Iliad or the Odyssey. There are already many such versions; but the best way for you, or any one else, to read Homer, is to read Homer. If you do not understand Greek, you can read him in one of the many English translations. You will find much of the spirit of the original in the translations by Bryant, by Lord Derby, and by old George Chapman, as well as in the admirable prose rendering by Butcher and Lang; but you can get none of it in any so-called simplified version.

My object in writing this “Story of the Golden Age” has been to pave the way, if I dare say it, to an enjoyable reading of Homer, either in translations or in the original. I have taken the various legends relating to the causes of the Trojan war, and, by assuming certain privileges never yet denied to story-tellers, have woven all into one continuous narrative, ending where Homer’s story begins. The hero of the Odyssey–a character not always to be admired or commended–is my hero. And, in telling the story of his boyhood and youth, I have taken the opportunity to repeat, for your enjoyment, some of the most beautiful of the old Greek myths. If I have, now and then, given them a coloring slightly different from the original, you will remember that such is the right of the story-teller, the poet, and the artist. The essential features of the stories remain unchanged. I have, all along, drawn freely from the old tragedians, and now and then from Homer himself; nor have I thought it necessary in every instance to mention authorities, or to apologize for an occasional close imitation of some of the best translations. The pictures of old Greek life have, in the main, been derived from the Iliad and the Odyssey, and will, I hope, help you to a better understanding of those poems when you come to make acquaintance directly with them.

Should you become interested in the “Story of the Golden Age,” as it is here related, do not be disappointed by its somewhat abrupt ending; for you will find it continued by the master-poet of all ages, in a manner both inimitable and unapproachable. If you are pleased with the discourse of the porter at the gate, how much greater shall be your delight when you stand in the palace of the king, and hearken to the song of the royal minstrel!

To the simple-hearted folk who dwelt in that island three thousand years ago, there was never a sweeter spot than sea-girt Ithaca. Rocky and rugged though it may have seemed, yet it was indeed a smiling land embosomed in the laughing sea. There the air was always mild and pure, and balmy with the breath of blossoms; the sun looked kindly down from a cloudless sky, and storms seldom broke the quiet ripple of the waters which bathed the shores of that island home. On every side but one, the land rose straight up out of the deep sea to meet the feet of craggy hills and mountains crowned with woods. Between the heights were many narrow dells green with orchards; while the gentler slopes were covered with vineyards, and the steeps above them gave pasturage to flocks of long-wooled sheep and mountain-climbing goats.

On that side of the island which lay nearest the rising sun, there was a fine, deep harbor; for there the shore bent inward, and only a narrow neck of land lay between the eastern waters and the western sea. Close on either side of this harbor arose two mountains, Neritus and Nereius, which stood like giant watchmen overlooking land and sea and warding harm away; and on the neck, midway between these mountains, was the king’s white palace, roomy and large, with blossoming orchards to the right and the left, and broad lawns in front, sloping down to the water’s edge.

Here, many hundreds of years ago, lived Laertes—a man of simple habits, who thought his little island home a kingdom large enough, and never sighed for a greater. Not many men had seen so much of the world as he; for he had been to Colchis with Jason and the Argonauts, and his feet had trod the streets of every city in Hellas. Yet in all his wanderings he had seen no fairer land than rocky Ithaca. His eyes had been dazzled by the brightness of the Golden Fleece, and the kings of Argos and of Ilios had shown him the gold and gems of their treasure-houses. Yet what cared he for wealth other than that which his flocks and vineyards yielded him? There was hardly a day but that he might be seen in the fields guiding his plough, or training his vines, or in his orchards pruning his trees, or gathering the mellow fruit. He had all the good gifts of life that any man needs; and for them he never failed to thank the great Giver, nor to render praises to the powers above. His queen, fair Anticleia, daughter of the aged chief Autolycus, was a true housewife, overseeing the maidens at their tasks, busying herself with the distaff and the spindle, or plying the shuttle at the loom; and many were the garments, rich with finest needlework, which her own fair fingers had fashioned.

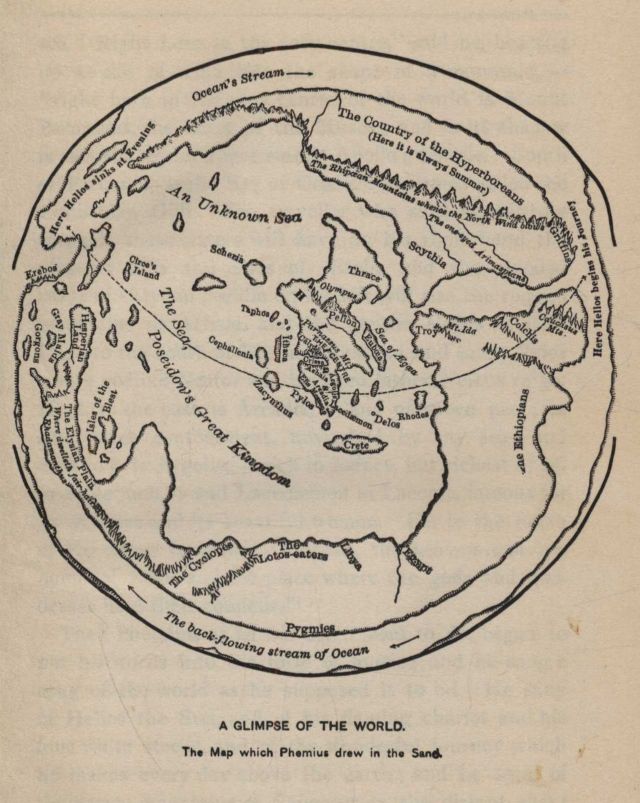

To Laertes and Anticleia one child had been born,–a son, who, they hoped, would live to bring renown to Ithaca. This boy, as he grew, became strong in body and mind far beyond his playfellows; and those who knew him wondered at the shrewdness of his speech no less than at the strength and suppleness of his limbs. And yet he was small of stature, and neither in face nor in figure was he adorned with any of Apollo’s grace. On the day that he was twelve years old, he stood with his tutor, the bard Phemius, on the top of Mount Neritus; below him, spread out like a great map, lay what was to him the whole world. Northward, as far as his eyes could see, there were islands great and small; and among them Phemius pointed out Taphos, the home of a sea-faring race, where Anchialus, chief of warriors, ruled. Eastward were other isles, and the low-lying shores of Acarnania, so far away that they seemed mere lines of hazy green between the purple waters and the azure sky. Southward beyond Samos were the wooded heights of Zacynthus, and the sea-paths which led to Pylos and distant Crete. Westward was the great sea, stretching away and away to the region of the setting sun; the watery kingdom of Poseidon, full of strange beings and unknown dangers,–a sea upon which none but the bravest mariners dared launch their ships.

The boy had often looked upon these scenes of beauty and mystery, but to-day his heart was stirred with an unwonted feeling of awe and of wonder at the greatness and grandeur of the world as it thus lay around him. Tears filled his eyes as he turned to his tutor. “How kind it was of the Being who made this pleasant earth, to set our own sunny Ithaca right in the centre of it, and to cover it all over with a blue dome like a tent!

[Note: This alludes to the time in the Biblical Creation Story when the Sky was separated from the Earth. In Ancient Greek Mythology, the primordial Gaea was the Earth and her son-mate Uranus was the Sky that domed above her. Later, Zeus became the ruler of the Sky.]

But tell me, do people live in all those lands that we see? I know that there are men dwelling in Zacynthus and in the little islands of the eastern sea; for their fishermen often come to Ithaca, and I have talked with them. And I have heard my father tell of his wonderful voyage to Colchis, which is in the region of the rising sun; and my mother often speaks of her old home in Parnassus, which also is far away towards the dawn. Is it true that there are men, women, and children, living in lands which we cannot see? and do the great powers above us care for them as for the good people of Ithaca? And is there anywhere another king so great as my father Laertes, or another kingdom so rich and happy as his?”

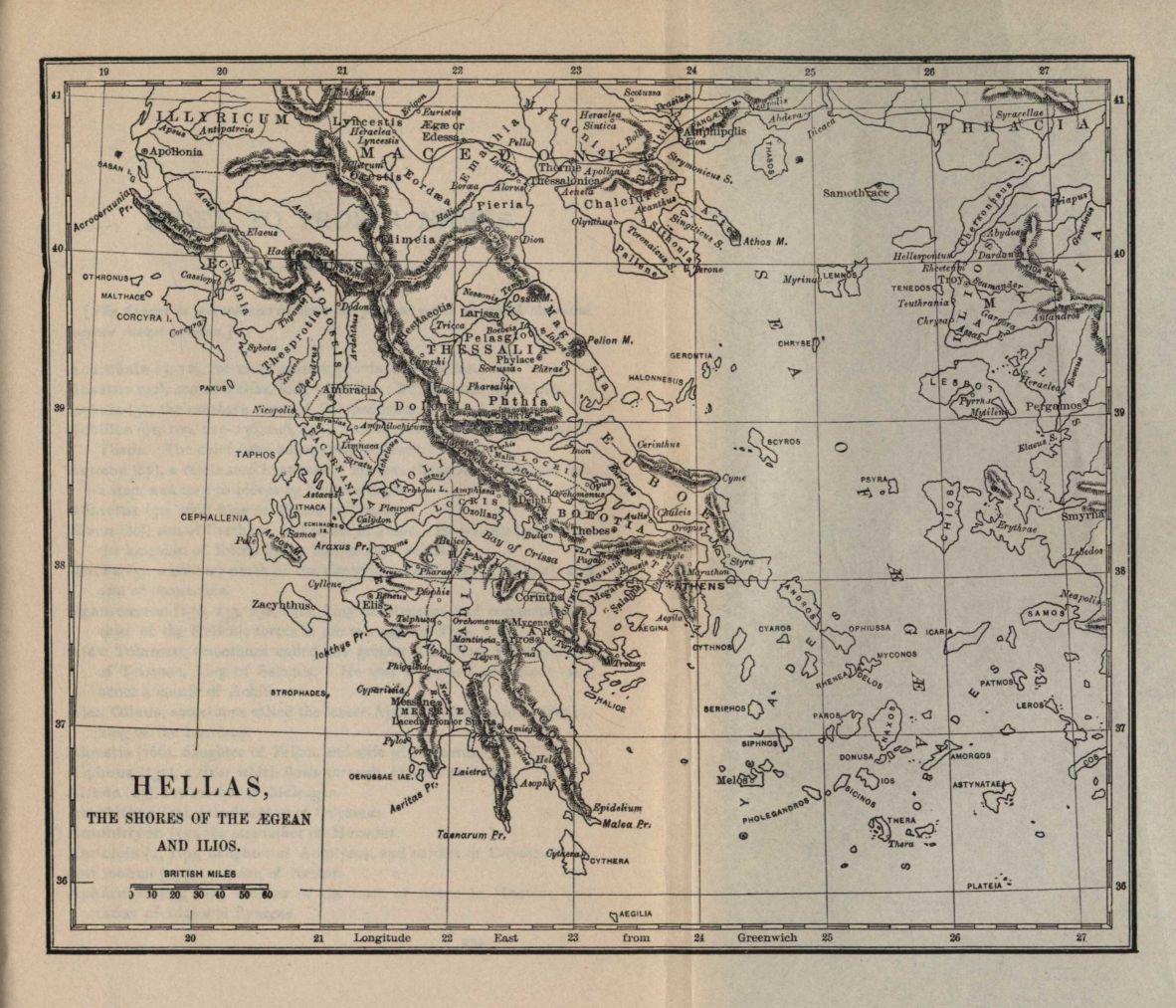

Then Phemius told the lad all about the land of the Hellenes beyond the narrow sea; and, in the sand at their feet, he drew with a stick a map of all the countries known to him.

The Map which Phemius drew in the Sand.

“We cannot see half of the world from this spot,” said the bard, “neither is Ithaca the centre of it, as it seems to you. I will draw a picture of it here in the sand, and show you where lies every land and every sea. Right here in the very centre,” said he, heaping up a pile of sand into the shape of a mountain,–“right here in the very centre of the world is Mount Parnassus, the home of the Muses; and in its shadow is sacred Delphi, where stands Apollo’s temple.

Image Credit: Greece Today

Barrow, Mandy. “Greece Today.” Ancient Greece, 3 Sept. 2022, www.primaryhomeworkhelp.co.uk/greece/today.html.

Image Credit: Bible Hub

“Corinth.” Bible Hub, bibleatlas.org/corinth.htm. Accessed 3 Sept. 2022.

South of Parnassus is the Bay of Crissa, sometimes called the Corinthian Gulf. The traveller who sails westwardly through those waters will have on his right hand the pleasant hills and dales of Ætolia and the wooded lands of Calydon; while on his left will rise the rugged mountains of Achaia, and the gentler slopes of Elis. Here to the south of Elis are Messene, and sandy Pylos where godlike Nestor and his aged father Neleus reign. Here, to the east, is Arcadia, a land of green pastures and sweet contentment, unwashed by any sea; and next to it is Argolis,–rich in horses, but richest of all in noble men,–and Lacedæmon in Laconia, famous for its warriors and its beautiful women. Far to the north of Parnassus is Mount Olympus, the heaven-towering home of Zeus, and the place where the gods and goddesses hold their councils.”

Image Credit: Pu Eble Rino – Not Verified Site

Then Phemius, as he was often wont to do, began to put his words into the form of music; and he sang a song of the world as he supposed it to be.

Helios – Sergey Panasenko-Mikhalkin

He sang of Helios the Sun, and of his flaming chariot and his four white steeds, and of the wonderful journey which he makes every day above the earth; and he sang of the snowy mountains of Caucasus in the distant east; and of the gardens of the Hesperides even farther to the westward; and of the land of the Hyperboreans, which lies beyond the northern mountains; and of the sunny climes where live the Ethiopians, the farthest distant of all earth’s dwellers. Then he sang of the flowing stream of Ocean which encircles all lands in its embrace; and, lastly, of the Islands of the Blest, where fair-haired Rhadamanthus rules, and where there is neither snow nor beating rains, but everlasting spring, and breezes balmy with the breath of life.

[Note: Oceanus was the primordial Sea that circled the known lands. ]

“O Phemius!” cried the boy, as the bard laid aside his harp, “I never knew that the world was so large. Can it be that there are so many countries and so many strange people beneath the same sky?”

“Yes,” answered Phemius, “the world is very broad, and our Ithaca is but one of the smallest of a thousand lands upon which Helios smiles, as he makes his daily journey through the skies. It is not given to one man to know all these lands; and happiest is he whose only care is for his home, deeming it the centre around which the world is built.”

“If only the half of what you have told me be true,” said the boy, “I cannot rest until I have seen some of those strange lands, and learned more about the wonderful beings which live in them. I cannot bear to think of being always shut up within the narrow bounds of little Ithaca.”

[Note: Odysseus is hearing the call of the Journey. The Journey is a Major Theme in Literature. In my opinion, The Hobbit is reminiscent of The Iliad. Compare also The Hero’s Journey by Joseph Campbell].

“My dear boy,” said Phemius, laughing, “your mind has been greatly changed within the past few moments. When we came here, a little while ago, you thought that Neritus was the grandest mountain in the world, and that Ithaca was the centre round which the earth was built. Then you were cheerful and contented; but now you are restless and unhappy, because you have learned of possibilities such as, hitherto, you had not dreamed about. Your eyes have been opened to see and to know the world as it is, and you are no longer satisfied with that which Ithaca can give you.”

“But why did you not tell me these things before?” asked the boy.

“It was your mother’s wish,” answered the bard, “that you should not know them until to-day. Do you remember what day this is?”

“It is my twelfth birthday. And I remember, too, that there was a promise made to my grandfather, that when I was twelve years old I should visit him in his strong halls on Mount Parnassus. I mean to ask my mother about it at once.”

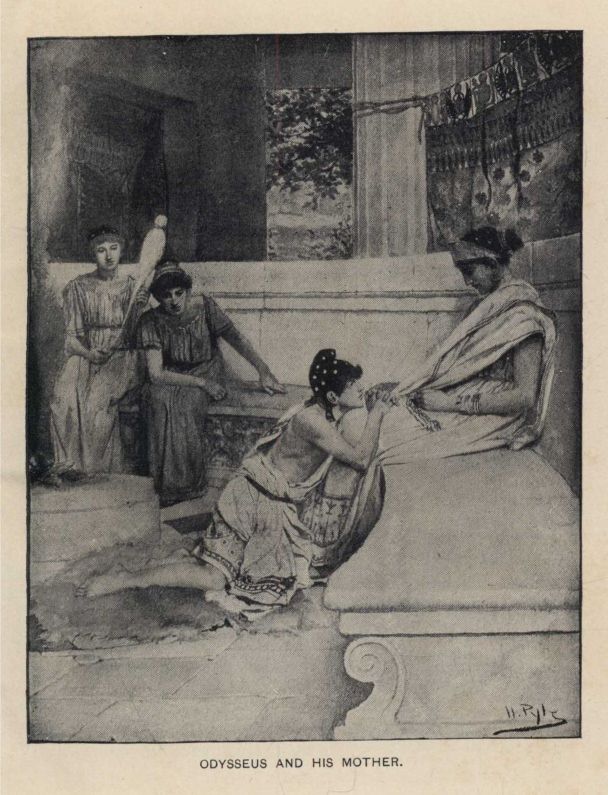

And without waiting for another word from Phemius, the lad ran hurriedly down the steep pathway, and was soon at the foot of the mountain. Across the fields he hastened, and through the vineyards where the vines, trained by his father’s own hand, were already hanging heavy with grapes. He found his mother in the inner hall, sitting before the hearth, and twisting from her distaff threads of bright sea-purple, while her maidens plied their tasks around her. He knelt upon the marble floor, and gently clasped his mother’s knees.

“Mother,” he said, “I come to ask a long-promised boon of you.”

“What is it, my son?” asked the queen, laying aside her distaff. “If there be any thing in Ithaca that I can give you, you shall surely have it.”

“I want nothing in Ithaca,” answered the boy; “I want to see more of this great world than I ever yet have known. And now that I am twelve years old, you surely will not forget the promise, long since made, that I should spend the summer with my grandfather at Parnassus. Let me go very soon, I pray; for I tire of this narrow Ithaca.”

The queen’s eyes filled with tears as she answered, “You shall have your wish, my son. The promise given both to you and to my father must be fulfilled. For, when you were but a little babe, Autolycus came to Ithaca. And one evening, as he feasted at your father’s table, your nurse, Dame Eurycleia, brought you into the hall, and put you into his arms. ‘Give this dear babe, O king, a name,’ said she. ‘He is thy daughter’s son, the heir to Ithaca’s rich realm; and we hope that he will live to make his name and thine remembered.’

“Then Autolycus smiled, and gently dandled you upon his knees. ‘My daughter, and my daughter’s lord,’ said he, ‘let this child’s name be Odysseus; for he shall visit many lands and climes, and wander long upon the tossing sea. Yet wheresoever the Fates may drive him, his heart will ever turn to Ithaca his home.

[Note: Home and the Return Home is another major Theme in Literature.]

Call him by the name which I have given; and when his twelfth birthday shall have passed, send him to my strong halls in the shadow of Parnassus, where his mother in her girlhood dwelt. Then I will share my riches with him, and send him back to Ithaca rejoicing!’ So spake my father, great Autolycus; and before we arose from that feast, we pledged our word that it should be with you even as he wished. And your name, Odysseus, has every day recalled to mind that feast and our binding words.”

“Oh that I could go at once, dear mother!” said Odysseus, kissing her tears away. “I would come home again very soon. I would stay long enough to have the blessing of my kingly grandfather; I would climb Parnassus, and listen to the sweet music of the Muses; I would drink one draught from the Castalian spring of which you have so often told me; I would ramble one day among the groves and glens, that perchance I might catch a glimpse of Apollo or of his huntress sister Artemis; and then I would hasten back to Ithaca, and would never leave you again.”

“My son,” then said Laertes, who had come unheard into the hall, and had listened to the boy’s earnest words,–“my son, you shall have your wish, for I know that the Fates have ordered it so. We have long looked forward to this day, and for weeks past we have been planning for your journey. My stanchest ship is ready to carry you over the sea, and needs only to be launched into the bay. Twelve strong oarsmen are sitting now upon the beach, waiting for orders to embark. To-morrow, with the bard Phemius as your friend and guide, you may set forth on your voyage to Parnassus. Let us go down to the shore at once, and offer prayers to Poseidon, ruler of the sea, that he may grant you favoring winds and a happy voyage.”

Odysseus kissed his mother again, and, turning, followed his father from the hall.

Then Anticleia rose, and bade the maidens hasten to make ready the evening meal; but she herself went weeping to her own chamber, there to choose the garments which her son should take with him upon his journey. Warm robes of wool, and a broidered tunic which she with her own hands had spun and woven, she folded and laid with care in a little wooden chest; and with them she placed many a little comfort, fruit and sweetmeats, such as she rightly deemed would please the lad. Then when she had closed the lid, she threw a strong cord around the chest, and tied it firmly down. This done, she raised her eyes towards heaven, and lifting up her hands, she prayed to Pallas Athené:–

[Note: Pallas Athené was the goddess Athena, who was the goddess of wisdom. Her father was Zeus, but at the time of her birth, she had no mother. She was birthed from Zeus’s head. Zeus had been suffering from a brutal headache. Zeus’s first wife was Metis, who represented both truth and cunning. The primordial deities Gaea and Uranus had visited Metis and had predicted to her that Zeus would have a son who would strip him of his power.

When Metis was about to give birth, Zeus remembered the prediction and challenged his wife. He asked her to a game of metamorphis. Metis changed herself several times until finally, she changed herself to a drop of water. Eager to end any threat that her child might dethrone him, Zeus drank the drop of water, and he thought that he had ended his threat. He was wrong. Later, he developed a severe headache. When Zeus could no longer stand the pain, he called upon all of the gods and goddesses to come and help him. One of his sons was Hephaestus-the Blacksmith. Hephaestus was a brute of a man, and he struck the spot of Zeus’s headache with his sledgehammer. A stream of blood flowed from Zeus’s head, and Athena sprang out of that stream. When the young girl Athena was born, she was fully armed and helmeted. She bellowed a deafening war cry, and all the other gods and goddesses were struck with fear. The rivers and the seas surged with riotous waves, and Helios reigned in his glorious steeds of fire.

The entire pantheon took note: the great Athena had been born, and she would change the world. Athena inherited the prudence and cunning of her mother Metis and the intelligence of her father Zeus. Athena would prove to be a great force. Although she was female, Athena was dedicated to the game of war. Athena would always be Zeus’s favorite child.

Zeus chose the river god Triton to take the responsibility for Athena’s education. Triton had a daughter who was the same age as Athena, and Athena and Pallas grew up to become best friends and near sisters, but tragedy struck.

While Triton was training the two girls for battle, Athena accidentally killed Pallas. Athena was devastated, and to honor her dear friend, she changed her own name to Pallas Athena. It was to Pallas Athena that the mother of Odysseus prayed.]

“O queen of the air and sky, hearken to my prayer, and help me lay aside the doubting fears which creep into my mind, and cause these tears to flow. For now my boy, unused to hardships, and knowing nothing of the world, is to be sent forth on a long and dangerous voyage. I tremble lest evil overtake him; but more I fear, that, with the lawless men of my father’s household, he shall forget his mother’s teachings, and stray from the path of duty. Do thou, O queen, go with him as his guide and guard, keep him from harm, and bring him safe again to Ithaca and his loving mother’s arms.”

Meanwhile Laertes and the men of Ithaca stood upon the beach, and offered up two choice oxen to Poseidon, ruler of the sea; and they prayed him that he would vouchsafe favoring winds and quiet waters and a safe journey to the bold voyagers who to-morrow would launch their ship upon the deep. And when the sun began to sink low down in the west, some sought their homes, and others went up to the king’s white palace to tarry until after the evening meal.

Cheerful was the feast; and as the merry jest went round, no one seemed more free from care than King Laertes. And when all had eaten of the food, and had tasted of the red wine made from the king’s own vintage, the bard Phemius arose, and tuned his harp, and sang many sweet and wonderful songs. He sang of the beginning of things; of the broad-breasted Earth, the mother of created beings; of the sky, and the sea, and the mountains; of the mighty race of Titans,–giants who once ruled the earth; of great Atlas, who holds the sky-dome upon his shoulders; of Cronos and old Oceanus; of the war which for ten years raged on Mount Olympus, until Zeus hurled his unfeeling father Cronos from the throne, and seized the sceptre for himself.

Hercules and Atlas painted by Lucas Cranach

[Note: Atlas was the titan who had been condemned to brace the sky dome of the world on his shoulders. Cronus was the supreme god until Zeus defeated and dethroned him. After that, Zeus became the supreme god. It is interesting that Cronus was a son born to Gaea and Uranus. When Uranus became vile and mean, Cronus overthrew Uranus. Cronus married his siter Rhea, and one of their sons was Zeus.]

When Phemius ended his singing, the guests withdrew from the hall, and each went silently to his own home; and Odysseus, having kissed his dear father and mother, went thoughtfully to his sleeping-room high up above the great hall. With him went his nurse, Dame Eurycleia, carrying the torches. She had been a princess once; but hard fate and cruel war had overthrown her father’s kingdom, and had sent her forth a captive and a slave. Laertes had bought her of her captors for a hundred oxen, and had given her a place of honor in his household next to Anticleia. She loved Odysseus as she would love her own dear child; for, since his birth, she had nursed and cared for him. She now, as was her wont, lighted him to his chamber; she laid back the soft coverings of his bed; she smoothed the fleeces, and hung his tunic within easy reach. Then with kind words of farewell for the night, she quietly withdrew, and closed the door, and pulled the thong outside which turned the fastening latch. Odysseus wrapped himself among the fleeces of his bed, and soon was lost in slumber.[1]

[1] See Note 1 at the end of this volume.

ADVENTURE II.

A VOYAGE ON THE SEA.

Early the next morning, while yet the dawn was waiting for the sun, Odysseus arose and hastened to make ready for his journey. The little galley which was to carry him across the sea had been already launched, and was floating close to the shore; and the oarsmen stood upon the beach impatient to begin the voyage. The sea-stores, and the little chest in which the lad’s wardrobe lay, were brought on board and placed beneath the rowers’ benches. The old men of Ithaca, and the boys and the maidens, hurried down to the shore, that they might bid the voyagers God-speed. Odysseus, when all was ready, spoke a few last kind words to his mother and sage Laertes, and then with a swelling heart went up the vessel’s side, and sat down in the stern. And Phemius the bard, holding his sweet-toned harp, followed him, and took his place in the prow. Then the sailors loosed the moorings, and went on board, and, sitting on the rowers’ benches, wielded the long oars; and the little vessel, driven by their well-timed strokes, turned slowly about, and then glided smoothly across the bay; and the eyes of all on shore were wet with tears as they prayed the rulers of the air and the sea that the voyagers might reach their wished-for port in safety, and in due time come back unharmed to Ithaca.

No sooner had the vessel reached the open sea, than Pallas Athené sent after it a gentle west wind to urge it on its way. As the soft breeze, laden with the perfumes of blossoming orchards, stirred the water into rippling waves, Phemius bade the rowers lay aside their oars, and hoist the sail. They heeded his behest, and lifting high the slender mast, they bound it in its place; then they stretched aloft the broad white sail, and the west wind caught and filled it, and drove the little bark cheerily over the waves. And the grateful crew sat down upon the benches, and with Odysseus and Phemius the bard, they joined in offering heartfelt thanks to Pallas Athené, who had so kindly prospered them. And by and by Phemius played soft melodies on his harp, such as the sea-nymphs liked to hear. And all that summer day the breezes whispered in the rigging, and the white waves danced in the vessel’s wake, and the voyagers sped happily on their way.

In the afternoon, when they had begun somewhat to tire of the voyage, Phemius asked Odysseus what they should do to lighten the passing hours.

“Tell us some story of the olden time,” said Odysseus. And the bard, who was never better pleased than when recounting some wonderful tale, sat down in the midships, where the oarsmen could readily hear him, and told the strange story of Phaethon, the rash son of Helios Hyperion.

The Fall of Phaethon – Painted by Peter Paul Rubens

Helios as Personification of Midday Anton Raphael Mengs (1728–1779)

“Among the immortals who give good gifts to men, there is no one more kind than Helios, the bestower of light and heat. Every morning when the Dawn with her rosy fingers illumes the eastern sky, good Helios rises from his golden couch, and from their pasture calls his milk-white steeds. By name he calls them,–

“‘Eos, Æthon, Bronté, Astrape!’

“Each hears his master’s voice, and comes obedient. Then about their bright manes and his own yellow locks he twines wreaths of sweet-smelling flowers,–amaranths and daffodils and asphodels from the heavenly gardens. And the Hours come and harness the steeds to the burning sun-car, and put the reins into Helios Hyperion’s hands. He mounts to his place, he speaks,–and the winged team soars upward into the morning air; and all earth’s children awake, and give thanks to the ruler of the Sun for the new day which smiles down upon them.

“Hour after hour, with steady hand, Helios guides his steeds; and the flaming car is borne along the sun-road through the sky. And when the day’s work is done, and sable night comes creeping over the earth, the steeds, the car, and the driver sink softly down to the western Ocean’s stream, where a golden vessel waits to bear them back again, swiftly and unseen, to the dwelling of the Sun in the east. There, under the home-roof, Helios greets his mother and his wife and his dear children; and there he rests until the Dawn again leaves old Ocean’s bed, and blushing comes to bid him journey forth anew.

“One son had Helios, Phaethon the Gleaming, and among the children of men there was no one more fair. And the great heart of Helios beat with love for his earth-child, and he gave him rich gifts, and kept nothing from him.

“And Phaethon, as he grew up, became as proud as he was fair, and wherever he went he boasted of his kinship to the Sun; and men when they looked upon his matchless form and his radiant features believed his words, and honored him as the heir of Helios Hyperion. But one Epaphos, a son of Zeus, sneered.

“‘Thou a child of Helios!’ he said; ‘what folly! Thou canst show nothing wherewith to prove thy kinship, save thy fair face and thy yellow hair; and there are many maidens in Hellas who have those, and are as beautiful as thou. Manly grace and handsome features are indeed the gifts of the gods; but it is by godlike deeds alone that one can prove his kinship to the immortals. While Helios Hyperion–thy father, as thou wouldst have it–guides his chariot above the clouds, and showers blessings upon the earth, what dost thou do? What, indeed, but dally with thy yellow locks, and gaze upon thy costly clothing, while all the time thy feet are in the dust, and the mire of the earth holds them fast? If thou hast kinship with the gods, prove it by doing the deeds of the gods! If thou art Helios Hyperion’s son, guide for one day his chariot through the skies.’

“Thus spoke Epaphos. And the mind of Phaethon was filled with lofty dreams; and, turning away from the taunting tempter, he hastened to his father’s house.

“Never-tiring Helios, with his steeds and car, had just finished the course of another day; and with words of warmest love he greeted his earth-born son.

“‘Dear Phaethon,’ he said, ‘what errand brings thee hither at this hour, when the sons of men find rest in slumber? Is there any good gift that thou wouldst have? Say what it is, and it shall be thine.’

“And Phaethon wept. And he said, ‘Father, there are those who say that I am not thy son. Give me, I pray thee, a token whereby I can prove my kinship to thee.’

“And Helios answered, ‘Mine it is to labor every day, and short is the rest I have, that so earth’s children may have light and life. Yet tell me what token thou cravest, and I swear that I will give it thee.’

“‘Father Helios,’ said the youth, ‘this is the token that I ask: Let me sit in thy place to-morrow, and drive thy steeds along the pathway of the skies.’

“Then was the heart of Helios full sad, and he said to Phaethon, ‘My child, thou knowest not what thou askest. Thou art not like the gods; and there lives no man who can drive my steeds, or guide the sun-car through the skies. I pray thee ask some other boon.’

“But Phaethon would not.

“‘I will have this boon or none. I will drive thy steeds to-morrow, and thereby make proof of my birthright.’

“Then Helios pleaded long with his son that he would not aspire to deeds too great for weak man to undertake. But wayward Phaethon would not hear. And when the Dawn peeped forth, and the Hours harnessed the steeds to the car, his father sadly gave the reins into his hands.

“‘My love for thee cries out, “Refrain, refrain!” Yet for my oath’s sake, I grant thy wish.’

“And he hid his face, and wept.

“And Phaethon leaped into the car, and lashed the steeds with his whip. Up they sprang, and swift as a storm cloud they sped high into the blue vault of heaven. For well did they know that an unskilled hand held the reins, and proudly they scorned his control.

“The haughty heart of Phaethon sank within him, and all his courage failed; and the long reins dropped from his nerveless grasp.

“‘Glorious father,’ he cried in agony, ‘thy words were true. Would that I had hearkened to thy warning, and obeyed!’

“And the sun-steeds, mad with their new-gained freedom, wildly careered in mid-heaven, and then plunged downward towards the earth. Close to the peopled plains they dashed and soared, dragging the car behind them. The parched earth smoked; the rivers turned to vaporous clouds; the trees shook off their scorched leaves and died; and men and beasts hid in the caves and rocky clefts, and there perished with thirst and the unbearable heat.

“‘O Father Zeus!’ prayed Mother Earth, ‘send help to thy children, or they perish through this man’s presumptuous folly!’

“Then the Thunderer from his high seat hurled his dread bolts, and unhappy Phaethon fell headlong from the car; and the fire-breathing steeds, affrighted but obedient, hastened back to the pastures of Helios on the shores of old Ocean’s stream.

“Phaethon fell into the river which men call Eridanos, and his broken-hearted sisters wept for him; and as they stood upon the banks and bewailed his unhappy fate, Father Zeus in pity changed them into tall green poplars; and their tears, falling into the river, were hardened into precious yellow amber. But the daughters of Hesperus, through whose country this river flows, built for the fair hero a marble tomb, close by the sounding sea. And they sang a song about Phaethon, and said that although he had been hurled to the earth by the thunderbolts of angry Zeus, yet he died not without honor, for he had his heart set on the doing of great deeds.”

As Phemius ended his story, Odysseus, who had been too intent upon listening to look around him, raised his eyes and uttered a cry of joy; for he saw that they had left the open sea behind them, and were entering the long and narrow gulf between Achaia and the Ætolian land. The oarsmen, who, too, had been earnest listeners, sprang quickly to their places, and hastened to ply their long oars; for now the breeze had begun to slacken, and the sail hung limp and useless upon the ship’s mast. Keeping close to the northern shore they rounded capes and headlands, and skirted the mouths of deep inlets, where Phemius said strange monsters often lurked in wait for unwary or belated seafarers. But they passed all these places safely, and saw no living creature, save some flocks of sea-birds flying among the cliffs, and one lone, frightened fisherman, who left his net upon the sands, and ran to hide himself in the thickets of underbrush which skirted the beach.

Late in the day they came to the mouth of a little harbor which, like one in Ithaca, was a favored haunt of old Phorcys the elder of the sea. Here the captain of the oarsmen said they must tarry for the night, for the sun was already sinking in the west, and after nightfall no ship could be guided with safety along these shores. A narrow strait between high cliffs led into the little haven, which was so sheltered from the winds that vessels could ride there without their hawsers, even though fierce storms might rage upon the sea outside. Through this strait the ship was guided, urged by the strong arms of the rowers; and so swiftly did it glide across the harbor that it was driven upon the shelving beach at the farther side, and stopped not until it lay full half its length high upon the warm, dry sand.

Then the crew lifted out their store of food, and their vessels for cooking; and while some took their bows and went in search of game, others kindled a fire, and hastened to make ready the evening meal. Odysseus and his tutor, when they had climbed out of the ship, sauntered along the beach, intent to know what kind of place it was to which fortune had thus brought them. They found that it was in all things a pattern and counterpart of the little bay of Phorcys in their own Ithaca.[1]

[1] See the description of this bay, in the Odyssey, Book xiii. l. 102.

Near the head of the harbor grew an olive tree, beneath whose spreading branches there was a cave, in which, men said, the Naiads sometimes dwelt. In this cave were great bowls and jars and two-eared pitchers, all of stone; and in the clefts of the rock the wild bees had built their comb, and filled it with yellow honey. In this cave, too, were long looms on which, from their spindles wrought of stone, the Naiads were thought to weave their purple robes. Close by the looms, a torrent of sweet water gushed from the rock, and flowed in crystal streams down into the bay. Two doorways opened into the cave: one from the north, through which mortal man might enter, and one from the south, kept as the pathway of Phorcys and the Naiads. But Odysseus and his tutor saw no signs of any of these beings: it seemed as if the place had not been visited for many a month.

After the voyagers had partaken of their meal, they sat for a long time around the blazing fire upon the beach, and each told some marvellous story of the sea. For their thoughts were all upon the wonders of the deep.

“We should not speak of Poseidon, the king of waters,” said the captain, “save with fear upon our lips, and reverence in our hearts. For he it is who rules the sea, as his brother Zeus controls the land; and no one dares to dispute his right. Once, when sailing on the Ægæan Sea, I looked down into the depths, and saw his lordly palace,–a glittering, golden mansion, built on the rocks at the bottom of the mere. Quickly did we spread our sails aloft, and the friendly breezes and our own strong arms hurried us safely away from that wonderful but dangerous station. In that palace of the deep, Poseidon eats and drinks and makes merry with his friends, the dwellers in the sea; and there he feeds and trains his swift horses,–horses with hoofs of bronze and flowing golden manes. And when he harnesses these steeds to his chariot, and wields above them his well-wrought lash of gold, you should see, as I have seen, how he rides in terrible majesty above the waves. And the creatures of the sea pilot him on his way, and gambol on either side of the car, and follow dancing in his wake. But when he smites the waters with the trident which he always carries in his hand, the waves roll mountain high, the lightnings flash, and the thunders peal, and the earth is shaken to its very core. Then it is that man bewails his own weakness, and prays to the powers above for help and succor.”

“I have never seen the palace of Poseidon,” said the helmsman, speaking slowly; “but once, when sailing to far-off Crete, our ship was overtaken by a storm, and for ten days we were buffeted by winds and waves, and driven into unknown seas. After this, we vainly tried to find again our reckonings, but we knew not which way to turn our vessel’s prow. Then, when the storm had ended, we saw upon a sandy islet great troops of seals and sea-calves couched upon the beach, and basking in the warm rays of the sun.

“‘Let us cast anchor, and wait here,’ said our captain; ‘for surely Proteus, the old man of the sea who keeps Poseidon’s herds, will come erewhile to look after these sea-beasts.’

“And he was right; for at noonday the herdsman of the sea came up out of the brine, and went among his sea-calves, and counted them, and called each one by name. When he was sure that not even one was missing, he lay down among them upon the sand. Then we landed quickly from our vessel, and rushed silently upon him, and seized him with our hands. The old master of magic tried hard to escape from our clutches, and did not forget his cunning. First he took the form of a long-maned lion, fierce and terrible; but when this did not affright us, he turned into a scaly serpent; then into a leopard, spotted and beautiful; then into a wild boar, with gnashing tusks and foaming mouth. Seeing that by none of these forms he could make us loosen our grasp upon him, he took the shape of running water, as if to glide through our fingers; then he became a tall tree full of leaves and blossoms; and, lastly, he became himself again. And he pleaded with us for his freedom, and promised to tell us any thing that we desired, if we would only let him go.

“‘Tell us which way we shall sail, and how far we shall go, that we may surely reach the fair harbor of Crete,’ said our captain.

“‘Sail with the wind two days,’ said the elder of the sea, ‘and on the third morning ye shall behold the hills of Crete, and the pleasant port which you seek.’

“Then we loosened our hold upon him, and old Proteus plunged into the briny deep; and we betook ourselves to our ship, and sailed away before the wind. And on the third day, as he had told us, we sighted the fair harbor of Crete.”

As the helmsman ended his story, his listeners smiled; for he had told them nothing but an old tale, which every seaman had learned in his youth,–the story of Proteus, symbol of the ever-changing forms of matter. Just then Odysseus heard a low, plaintive murmur, seeming as if uttered by some lost wanderer away out upon the sea.

“What is that?” he asked, turning towards Phemius.

“It is Glaucus, the soothsayer of the sea, lamenting that he is mortal,” answered the bard. “Long time ago, Glaucus was a poor fisherman who cast his nets into these very waters, and built his hut upon the Ætolian shore, not very far from the place where we now sit. Before his hut there was a green, grassy spot, where he often sat to dress the fish which he caught. One day he carried a basketful of half-dead fish to that spot, and turned them out upon the ground. Wonderful to behold! Each fish took a blade of grass in its mouth, and forthwith jumped into the sea. The next day he found a hare in the woods, and gave chase to it. The frightened creature ran straight to the grassy plat before his hut, seized a green spear of grass between its lips, and dashed into the sea.

“‘Strange what kind of grass that is!’ cried Glaucus. Then he pulled up a blade, and tasted it. Quick as thought, he also jumped into the sea; and there he wanders evermore among the seaweeds and the sand and the pebbles and the sunken rocks; and, although he has the gift of soothsaying, and can tell what things are in store for mortal men, he mourns and laments because he cannot die.”

Then Phemius, seeing that Odysseus grew tired of his story, took up his harp, and touched its strings, and sang a song about old Phorcys,–the son of the Sea and Mother Earth,–and about his strange daughters who dwell in regions far remote from the homes of men.

He touched his harp lightly, and sang a sweet lullaby,–a song about the Sirens, the fairest of all the daughters of old Phorcys. These have their home in an enchanted island in the midst of the western sea; and they sit in a green meadow by the shore, and they sing evermore of empty pleasures and of phantoms of delight and of vain expectations. And woe is the wayfaring man who hearkens to them! for by their bewitching tones they lure him to his death, and never again shall he see his dear wife or his babes, who wait long and vainly for his home-coming. Stop thine ears, O voyager on the sea, and listen not to the songs of the Sirens, sing they ever so sweetly; for the white flowers which dot the meadow around them are not daisies, but the bleached bones of their victims.

Then Phemius smote the chords of his harp, and played a melody so weird and wild that Odysseus sprang to his feet, and glanced quickly around him, as if he thought to see some grim and horrid shape threatening him from among the gathering shadows. And this time the bard sang a strange, tumultuous song, concerning other daughters of old Phorcys,–the three Gray Sisters, with shape of swan, who have but one tooth for all, and one common eye, and who sit forever on a barren rock near the farthest shore of Ocean’s stream. Upon them the sun doth never cast a beam, and the moon doth never look; but, horrible and alone, they sit clothed in their yellow robes, and chatter threats and meaningless complaints to the waves which dash against their rock.

Not far away from these monsters once sat the three Gorgons, daughters also of old Phorcys. These were clothed with bat-like wings, and horror sat upon their faces. They had ringlets of snakes for hair, and their teeth were like the tusks of swine, and their hands were talons of brass; and no mortal could ever gaze upon them and breathe again. But there came, one time, a young hero to those regions,–Perseus the godlike; and he snatched the eye of the three Gray Sisters, and flung it far into the depths of Lake Tritonis; and he slew Medusa, the most fearful of the Gorgons, and carried the head of the terror back to Hellas with him as a trophy.

The bard chose next a gentler theme: and, as he touched his harp, the listeners fancied that they heard the soft sighing of the south wind, stirring lazily the leaves and blossoms; they heard the plashing of fountains, and the rippling of water-brooks, and the songs of little birds; and their minds were carried away in memory to pleasant gardens in a summer land. And Phemius sang of the Hesperides, or the maidens of the West, who also, men say, are the daughters of Phorcys the ancient. The Hesperian land in which they dwell is a country of delight, where the trees are laden with golden fruit, and every day is a sweet dream of joy and peace. And the clear-voiced Hesperides sing and dance in the sunlight always; and their only task is to guard the golden apples which grow there, and which Mother Earth gave to Here the queen upon her wedding day.

Here Phemius paused. Odysseus, lulled by the soft music, and overcome by weariness, had lain down upon the sand and fallen asleep. At a sign from the bard, the seamen lifted him gently into the ship, and, covering him with warm skins, they left him to slumber through the night.

ADVENTURE III.

THE CENTRE OF THE EARTH.

The next morning, before the sun had risen, the voyagers launched their ship again, and sailed out of the little harbor into the long bay of Crissa. And Pallas Athené sent the west wind early, to help them forward on their way; and they spread their sail, and instead of longer hugging the shore, they ventured boldly out into the middle of the bay. All day long the ship held on its course, skimming swiftly through the waves like a great white-winged bird; and those on board beguiled the hours with song and story as on the day before. But when the evening came, they were far from land; and the captain said that as the water was deep, and he knew the sea quite well, they would not put into port, but would sail straight on all night. And so, when the sun had gone down, and the moon had risen, flooding earth and sea with her pure, soft light, Odysseus wrapped his warm cloak about him, and lay down again to rest upon his bed of skins between the rowers’ benches. But the helmsman stood at his place, and guided the vessel over the shadowy waves; and through the watches of the night the west wind filled the sails, and the dark keel of the little bark ploughed the waters, and Pallas Athené blessed the voyage.

When, at length, the third morning came, and Helios arose at summons of the Dawn, Odysseus awoke. To his great surprise, he heard no longer the rippling of the waves upon the vessel’s sides, nor the flapping of the sail in the wind, nor yet the rhythmic dipping of the oars into the sea. He listened, and the sound of merry laughter came to his ears, and he heard the twittering of many birds, and the far-away bleating of little lambs. He rubbed his eyes, and sat up, and looked about him. The ship was no longer floating on the water, but had been drawn high up on a sandy beach; and the crew were sitting beneath an olive tree, at no great distance from the shore, listening to the melodies with which a strangely-garbed shepherd welcomed on his flute the coming of another day.

Odysseus arose quickly and leaped out upon the beach. Then it was that a scene of beauty and quiet grandeur met his gaze,–a scene, the like of which had never entered his thoughts nor visited his dreams. He saw, a few miles to the northward, a group of high mountains whose summits towered above the clouds; and highest among them all were twin peaks whose snow-crowned tops seemed but little lower than the skies themselves. And as the light of the newly risen sun gilded the gray crags, and painted the rocky slopes, and shone bright among the wooded uplands, the whole scene appeared like a living picture, glorious with purple and gold and azure, and brilliant with sparkling gems.

“Is it not truly a fitting place for the home of beauty and music, the dwelling of Apollo, and the favored haunt of the Muses?” asked Phemius, drawing near, and observing the boy’s wondering delight.

“Indeed it is,” said Odysseus, afraid to turn his eyes away, lest the enchanting vision should vanish like a dream. “But is that mountain really Parnassus, and is our journey so nearly at an end?”

“Yes,” answered the bard, “that peak which towers highest toward the sky is great Parnassus, the centre of the earth; and in the rocky cleft which you can barely see between the twin mountains, stands sacred Delphi and the favored temple of Apollo. Lower down, and on the other side of the mountain, is the white-halled dwelling of old Autolycus, your mother’s father. Although the mountain seems so near, it is yet a long and toilsome journey thither,–a journey which we must make on foot, and by pathways none the safest. Come, let us join the sailors under the olive tree; and when we have breakfasted, we will begin our journey to Parnassus.”

The strange shepherd had killed the fattest sheep of his flock, and had roasted the choicest parts upon a bed of burning coals; and when Odysseus and his tutor came to the olive tree, they found a breakfast fit indeed for kings, set out ready before them.

“Welcome, noble strangers,” said the shepherd; “welcome to the land most loved of the Muses. I give you of the best of all that I have, and I am ready to serve you and do your bidding.”

Phemius thanked the shepherd for his kindness; and while they sat upon the grass, and ate of the pleasant food which had been provided, he asked the simple swain many questions about Parnassus.

“I have heard that Parnassus is the hub around which the great earth-wheel is built. Is it really true?”

“A long, long time ago,” answered the man, “there were neither any shepherds nor sheep in Hellas, and not even the gods knew where the centre of the earth had been put. Some said that it was at Mount Olympus, where Zeus sits in his great house with all the deathless ones around him. Others said that it was in Achaia; and others still, in Arcadia, now the land of shepherds; and some, who, it seems to me, had lost their wits, said that it was not in Hellas at all, but in a strange land beyond the western sea. In order that he might know the truth, great Zeus one day took two eagles, both of the same strength and swiftness, and said, ‘These birds shall tell us what even the gods do not know.’ Then he carried one of the eagles to the far east, where the Dawn rises out of Ocean’s bed; and he carried the other to the far west where Helios and his sun-car sink into the waves; and he clapped his hands together, and the thunder rolled, and the swift birds flew at the same moment to meet each other; and right above the spot where Delphi stands, they came together, beak to beak, and both fell dead to the ground. ‘Behold! there is the centre of the earth,’ said Zeus. And all the gods agreed that he was right.”

“Do you know the best and shortest road to Delphi?” asked Phemius.

“No one knows it better than I,” was the answer. “When I was a boy I fed my sheep at the foot of Parnassus; and my father and grandfather lived there, long before the town of Delphi was built, or there was any temple there for Apollo. Shall I tell you how men came to build a temple at that spot?”

“Yes, tell us,” said Odysseus. “I am anxious to know all about it.”

“You must not repeat my story to the priests at Delphi,” said the shepherd, speaking now in a lower tone. “For they have quite a different way of telling it, and they would say that I have spoken lightly of sacred things. There was a time when only shepherds lived on the mountain slopes, and there were neither priests nor warriors nor robbers in all this land. My grandfather was one of those happy shepherds; and he often pastured his flocks on the broad terrace where the town of Delphi now stands, and where the two eagles, which I have told you about, fell to the ground. One day, a strange thing happened to him. A goat which was nibbling the grass from the sides of a little crevice in the rock, fell into a fit, and lay bleating and helpless upon the ground. My grandfather ran to help the beast; but as he stooped down, he too fell into a fit, and he saw strange visions, and spoke prophetic words. Some other shepherds who were passing by saw his plight, and lifted him up; and as soon as he breathed the fresh air, he was himself again.

“Often after this, the same thing happened to my grandfather’s goats; and when he had looked carefully into the matter, he found that a warm, stifling vapor issued at times from the crevice, and that it was the breathing of this vapor which had caused his goats and even himself to lose their senses. Then other men came; and they learned that by sitting close to the crevice, and inhaling its vapor, they gained the power to foresee things, and the gift of prophecy came to them. And so they set a tripod over the crevice for a seat, and they built a temple–small at first–over the tripod; and they sent for the wisest maidens in the land to come and sit upon the tripod and breathe the strange vapor, so that they could tell what was otherwise hidden from human knowledge. Some say that the vapor is the breath of a python, or great serpent; and they call the priestess who sits upon the tripod Pythia. But I know nothing about that.”

“Are you sure,” asked Phemius, “that it was your grandfather who first found that crevice in the rock?”

“I am not quite sure,” said the shepherd. “But I heard the story when I was a little child, and I know that it was either my grandfather or my grandfather’s grandfather. At any rate, it all happened many, many years ago.”

By this time they had finished their meal; and after they had given thanks to the powers who had thus far kindly prospered them, they hastened to renew their journey. Two of the oarsmen, who were landsmen as well as seamen, were to go with them to carry their luggage and the little presents which Laertes had sent to the priests at Delphi. The shepherd was to be their guide; and a second shepherd was to keep them company, so as to help them in case of need.

The sun was high over their heads when they were ready to begin their long and toilsome walk. The road at first was smooth and easy, winding through meadows and orchards and shady pastures. But very soon the way became steep and uneven, and the olive trees gave place to pines, and the meadows to barren rocks. The little company toiled bravely onward, however, the two shepherds leading the way and cheering them with pleasant melodies on their flutes, while the two sailors with their heavy loads followed in the rear.

It was quite late in the day when they reached the sacred town of Delphi, nestling in the very bosom of Parnassus. The mighty mountain wall now rose straight up before them, seeming to reach even to the clouds. The priests who kept the temple met them on the outskirts of the town, and kindly welcomed them for the sake of King Laertes, whom they knew and had seen; and they besought the wayfarers to abide for some time in Delphi. Nor, indeed, would Phemius have thought of going farther until he had prayed to bright Apollo, and offered rich gifts at his shrine, and questioned the Pythian priestess about the unknown future.

And so Odysseus and his tutor became the honored guests of the Delphian folk; and they felt that surely they were now at the very centre of the world. Their hosts dealt so kindly with them, that a whole month passed, and still they were in Delphi. And as they talked with the priests in the temple, or listened to the music of the mountain nymphs, or drank sweet draughts of wisdom from the Castalian spring, they every day found it harder and harder to tear themselves away from the delightful place.

ADVENTURE IV.

THE SILVER-BOWED APOLLO.

One morning Odysseus sat in the shadow of Parnassus with one of the priests of Apollo, and they talked of many wonderful things; and the boy began to think to himself that there was more wisdom in the words of his companion than in all the waters of the Castalian spring. He could see, from where he sat, the stream of that far-famed fountain, flowing out of the rocks between two cliffs, and falling in sparkling cascades down the steep slopes.

“Men think that they gain wisdom by drinking from that spring,” said he to the priest; “but I think that they gain it in quite another way. They drink of its waters every day; but while they drink, they listen to the wonderful words which fall from your lips, and they become wise by hearing, and not by drinking.”

The old priest smiled at the shrewdness of the boy. “Let them think as they please,” said he. “In any case, their wisdom would come hard, and be of little use, if it were not for the silver-bowed Apollo.”

“Tell me about Apollo,” said Odysseus.

The priest could not have been better pleased. He moved his seat, so that he could look the boy full in the face, and at the same time have the temple before him, and then he began:–

“A very long time ago, Apollo was born in distant Delos. And when the glad news of his birth was told, Earth smiled, and decked herself with flowers; the nymphs of Delos sang songs of joy that were heard to the utmost bounds of Hellas; and choirs of white swans flew seven times around the island, piping notes of praise to the pure being who had come to dwell among men. Then Zeus looked down from high Olympus, and crowned the babe with a golden head-band, and put into his hands a silver bow and a sweet-toned lyre such as no man had ever seen; and he gave him a team of white swans to drive, and bade him go forth to teach men the things which are right and good, and to make light that which is hidden and in darkness.

“And so Apollo arose, beautiful as the morning sun, and journeyed through many lands, seeking a dwelling-place. He stopped for a time at the foot of Mount Olympus, and played so sweetly upon his lyre that Zeus and all his court were entranced. Then he went into Pieria and Iolcos, and he wandered up and down through the whole length of the Thessalian land; but nowhere could he find a spot in which he was willing to dwell. Then he climbed into his car, and bade his swan-team fly with him to the country of the Hyperboreans beyond the far-off northern mountains. Forthwith they obeyed; and through the pure regions of the upper air they bore him, winging their way ever northward. They carried him over the desert flats where the shepherd folk of Scythia dwell in houses of wicker-work perched on well-wheeled wagons, and daily drive their flocks and herds to fresher pastures. They carried him over that unknown land where the Arimaspian host of one-eyed horsemen dwell beside a river running bright with gold; and on the seventh day they came to the great Rhipæan Mountains where the griffins, with lion bodies and eagle wings, guard the golden treasures of the North. In these mountains, the North Wind has his home; and from his deep caves he now and then comes forth, chilling with his cold and angry breath the orchards and the fair fields of Hellas, and bringing death and dire disasters in his train. But northward this blustering Boreas cannot blow, for the heaven-towering mountains stand like a wall against him, and drive him back; and hence it is that beyond these mountains the storms of winter never come, but one happy springtime runs through all the year. There the flowers bloom, and the grain ripens, and the fruits drop mellowing to the earth, and the red wine is pressed from the luscious grape, every day the same. And the Hyperboreans who dwell in that favored land know neither pain nor sickness, nor wearying labor nor eating care; but their youth is as unfading as the springtime, and old age with its wrinkles and its sorrows is evermore a stranger to them. For the spirit of evil, which leads all men to err, has never found entrance among them, and they are free from vile passions and unworthy thoughts; and among them there is neither war, nor wicked deeds, nor fear of the avenging Furies, for their hearts are pure and clean, and never burdened with the love of self.

“When the swan-team of silver-bowed Apollo had carried him over the Rhipæan Mountains, they alighted in the Hyperborean land. And the people welcomed Apollo with shouts of joy and songs of triumph, as one for whom they had long been waiting. And he took up his abode there, and dwelt with them one whole year, delighting them with his presence, and ruling over them as their king. But when twelve moons had passed, he bethought him that the toiling, suffering men of Hellas needed most his aid and care. Therefore he bade the Hyperboreans farewell, and again went up into his sun-bright car; and his winged team carried him back to the land of his birth.

“Long time Apollo sought a place where he might build a temple to which men might come to learn of him and to seek his help in time of need. At length he came to the plain of fair Tilphussa, by the shore of Lake Copais; and there he began to build a house, for the land was a pleasant one, well-watered, and rich in grain and fruit. But the nymph Tilphussa liked not to have Apollo dwell so near her, lest men seeing and loving him should forget to honor her; and one day garmented with mosses and crowned with lilies, she came and stood before him in the sunlight.

“‘Apollo of the silver bow,’ said she, ‘have you not made a mistake in choosing this place for a dwelling? These rich plains around us will not always be as peaceful as now; for their very richness will tempt the spoiler, and the song of the cicada will then give place to the din of battle. Even in times of peace, you would hardly have a quiet hour here: for great herds of cattle come crowding down every day to my lake for water; and the noisy ploughman, driving his team afield, disturbs the morning hour with his boorish shouts; and boys and dogs keep up a constant din, and make life in this place a burden.’

“‘Fair Tilphussa,’ said Apollo, ‘I had hoped to dwell here in thy happy vale, a neighbor and friend to thee. Yet, since this place is not what it seems to be, whither shall I go, and where shall I build my house?”

“‘Go to the cleft in Parnassus where the swift eagles of Zeus met above the earth’s centre,’ answered the nymph. ‘There thou canst dwell in peace, and men will come from all parts of the world to do thee honor.’

“And so Apollo came down towards Crissa, and here in the cleft of the mountain he laid the foundations of his shrine. Then he called the master-architects of the world, Trophonius and Agamedes, and gave to them the building of the high walls and the massive roof. And when they had finished their work, he said, ‘Say now what reward you most desire for your labor, and I will give it you.’

“‘Give us,’ said the brothers, ‘that which is the best for men.’

“‘It is well,’ answered Apollo. ‘When the full moon is seen above the mountain-tops, you shall have your wish.”

“But when the moon rose full and clear above the heights, the two brothers were dead.

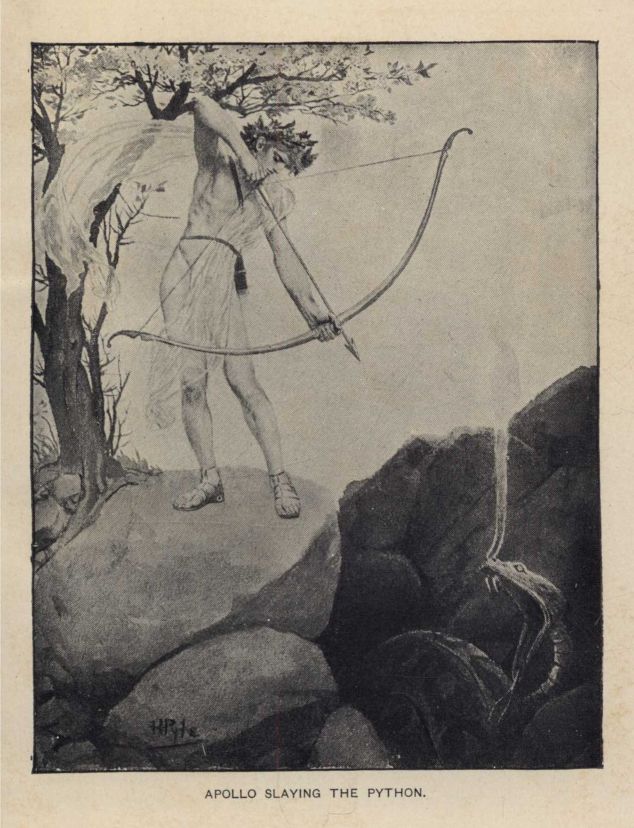

“And Apollo was pleased with the place which he had chosen for a home; for here were peace and quiet, and neither the hum of labor nor the din of battle would be likely ever to enter. Yet there was one thing to be done before he could have perfect rest. There lived near the foot of the mountain a huge serpent called Python, which was the terror of all the land. Oftentimes, coming out of his den, this monster attacked the flocks and herds, and sometimes even their keepers; and he had been known to carry little children and helpless women to his den, and there devour them.

“The men of Delphi came one day to Apollo, and prayed him to drive out or destroy their terrible enemy. So, taking in hand his silver bow, he sallied out at break of day to meet the monster when he should issue from his slimy cave. The vile creature shrank back when he saw the radiant god before him, and would fain have hidden himself in the deep gorges of the mountain. But Apollo quickly launched a swift arrow at him, crying, ‘Thou bane of man, lie thou upon the earth, and enrich it with thy dead body!’ And the never-erring arrow sped to the mark; and the great beast died, wallowing in his gore. And the people in their joy came out to meet the archer, singing pæans in his praise; and they crowned him with wild flowers and wreaths of olives, and hailed him as the Pythian king; and the nightingales sang to him in the groves, and the swallows and cicadas twittered and tuned their melodies in harmony with his lyre.[1]

[1] See Note 2 at the end of this volume.

“But as yet there were no priests in Apollo’s temple; and he pondered, long doubting, as to whom he should choose. One day he stood upon the mountain’s top-most peak, whence he could see all Hellas and the seas around it. Far away in the south, he spied a little ship sailing from Crete to sandy Pylos; and the men who were on board were Cretan merchants.

“‘These men shall serve in my temple!’ he cried.

“Upward he sprang, and high he soared above the sea; then swiftly descending like a fiery star, he plunged into the waves. There he changed himself into the form of a dolphin, and swam with speed to overtake the vessel. Long before the ship had reached Pylos, the mighty fish came up with it, and struck its stern. The crew were dumb with terror, and sat still in their places; their oars were motionless; the sail hung limp and useless from the mast. Yet the vessel sped through the waves with the speed of the wind, for the dolphin was driving it forward by the force of his fins. Past many a headland, past Pylos and many pleasant harbors, they hastened. Vainly did the pilot try to land at Cyparissa and at Cyllene: the ship would not obey her helm. They rounded the headland of Araxus, and came into the long bay of Crissa; and there the dolphin left off guiding the vessel, and swam playfully around it, while a brisk west wind filled the sail, and bore the voyagers safely into port.

“Then the dolphin changed into the form of a glowing star, which, shooting high into the heavens, lit up the whole world with its glory; and as the awe-stricken crew stood gazing at the wonder, it fell with the quickness of light upon Parnassus. Into his temple Apollo hastened, and there he kindled an undying fire. Then, in the form of a handsome youth, with golden hair falling in waves upon his shoulders, he hastened to the beach to welcome the Cretan strangers.

“‘Hail, seamen!’ he cried. ‘Who are you, and from whence do you come? Shall I greet you as friends and guests, or shall I know you as robbers bringing death and distress to many a fair home?’

“Then answered the Cretan captain, ‘Fair stranger, the gods have brought us hither; for by no wish of our own have we come. We are Cretan merchants, and we were on our way to sandy Pylos with stores of merchandise, to barter with the tradesmen of that city. But some unknown being, whose might is greater than the might of men, has carried us far beyond our wished-for port, even to this unknown shore. Tell us now, we pray thee, what land is this? And who art thou who lookest so like a god?’

“‘Friends and guests, for such indeed you must be,’ answered the radiant youth, ‘think never again of sailing upon the wine-faced sea, but draw now your vessel high up on the beach. And when you have brought out all your goods, and built an altar upon the shore, take of your white barley which you have with you, and offer it reverently to Phœbus Apollo. For I am he; and it was I who brought you hither, so that you might keep my temple, and make known my wishes unto men. And since it was in the form of a dolphin that you first saw me, let the town which stands around my temple be known as Delphi, and let men worship me there as Apollo Delphinius.’

“Then the Cretans did as he had bidden them: they drew their vessel high up on the white beach, and when they had unladen it of their goods, they built an altar on the shore, and offered white barley to Phœbus Apollo, and gave thanks to the ever-living powers who had saved them from the terrors of the deep. And after they had feasted, and rested from their long voyage, they turned their faces toward Parnassus; and Apollo, playing sweeter music than men had ever heard, led the way; and the folk of Delphi, with choirs of boys and maidens, came to meet them, and they sang a pæan and songs of victory as they helped the Cretans up the steep pathway to the cleft of Parnassus.

“‘I leave you now to have sole care of my temple,’ said Apollo. ‘I charge you to keep it well; deal righteously with all men; let no unclean thing pass your lips; forget self; guard well your thoughts, and keep your hearts free from guile. If you do these things, you shall be blessed with length of days and all that makes life glad. But if you forget my words, and deal treacherously with men, and cause any to wander from the path of right, then shall you be driven forth homeless and accursed, and others shall take your places in the service of my house.’

“And then the bright youth left them and hastened away into Thessaly and to Mount Olympus. But every year he comes again, and looks into his house, and speaks words of warning and of hope to his servants; and often men have seen him on Parnassus, playing his lyre to the listening Muses, or with his sister, arrow-loving Artemis, chasing the mountain deer.”

Such was the story which the old priest related to Odysseus, sitting in the shadow of the mountain; and the boy listened with eyes wide open and full of wonder, half expecting to see the golden-haired Apollo standing by his side.

ADVENTURE V.

THE KING OF CATTLE THIEVES.

Odysseus and his tutor tarried, as I have told you, a whole month at Delphi; for Phemius would not venture farther on their journey until the Pythian oracle should tell him how it would end. In the mean while many strangers were daily coming from all parts of Hellas, bringing rich gifts for Apollo’s temple, and seeking advice from the Pythia. From these strangers Odysseus learned many things concerning lands and places of which he never before had heard; and nothing pleased him better than to listen to the marvellous tales which each man told about his own home and people.

One day as he was walking towards the spring of Castalia, an old man, who had come from Corinth to ask questions of the Pythia, met him, and stopped to talk with him.

“Young prince,” said the old man, “what business can bring one so young as you to this place sacred to Apollo?”

“I am on my way to visit my grandfather,” said Odysseus, “and I have stopped here for a few days while my tutor consults the oracle.”

“Your grandfather! And who is your grandfather?” asked the old man.

“The great chief Autolycus, whose halls are on the other side of Parnassus,” answered Odysseus.

The old man drew a long breath, and after a moment’s silence said, “Perhaps, then, you are going to help your grandfather take care of his neighbors’ cattle.”

“I do not know what you mean,” answered Odysseus, startled by the tone in which the stranger spoke these words.

“I mean that your grandfather, who is the most cunning of men, will expect to teach you his trade,” said the man, with a strange twinkle in his eye.

“My grandfather is a chieftain and a hero,” said the boy. “What trade has he?”

“You pretend not to know that he is a cattle-dealer,” answered the old man, shrugging his shoulders. “Why, all Hellas has known him these hundred years as the King of Cattle Thieves! But he is very old now, and the herdsmen and shepherds have little to fear from him any more. Yet, mind my words, young prince: it does not require the wisdom of the Pythian oracle to foretell that you, his grandson, will become the craftiest of men. With Autolycus for your grandfather and Hermes for your great-grandfather, it would be hard indeed for you to be otherwise.”

At this moment the bard Phemius came up, and the old man walked quickly away.

“What does he mean?” asked Odysseus, turning to his tutor. “What does he mean by saying that my grandfather is the king of cattle thieves, and by speaking of Hermes as my great-grandfather?”

“They tell strange tales about Autolycus, the mountain chief,” Phemius answered; “but whether their stories be true or false, I cannot say. The old man who was talking to you is from Corinth, where once reigned Sisyphus, a most cruel and crafty king. From Corinth, Sisyphus sent ships and traders to all the world; and the wealth of Hellas might have been his, had he but loved the truth and dealt justly with his fellow-men. But there was no honor in his soul; he betrayed his dearest friends for gold; and he crushed under a huge block of stone the strangers who came to Corinth to barter their merchandise. It is said, that, once upon a time, Autolycus went down to Corinth in the night, and carried away all the cattle of Sisyphus, driving them to his great pastures beyond Parnassus. Not long afterward, Sisyphus went boldly to your grandfather’s halls, and said,–

“‘I have come, Autolycus, to get again my cattle which you have been so kindly pasturing.’

“‘It is well,’ said Autolycus. ‘Go now among my herds, and if you find any cattle bearing your mark upon them, they are yours: drive them back to your own pastures. This is the offer which I make to every man who comes claiming that I have stolen his cattle.’

“Then Sisyphus, to your grandfather’s great surprise, went among the herds, and chose his own without making a single error.

“‘See you not my initial, [sigma symbol], under the hoof of each of these beasts?’ asked Sisyphus.

“Autolycus saw at once that he had been outwitted, and he fain would have made friends with one who was more crafty than himself. But Sisyphus dealt treacherously with him, as he did with every one who trusted him. Yet men say, that, now he is dead, he has his reward in Hades; for there he is doomed to the never-ending toil of heaving a heavy stone to the top of a hill, only to see it roll back again to the plain.[1] It was from him that men learned to call your grandfather the King of Cattle Thieves; with how much justice, you may judge for yourself.”

[1] See Note 3 at the end of this volume.

“You have explained a part of what I asked you,” said Odysseus thoughtfully, “but you have not answered my question about Hermes.”

“I will answer that at another time,” said Phemius; “for to-morrow we must renew our journey, and I must go now and put every thing in readiness.”[2]

[2] See Note 4 at the end of this volume.

“But has the oracle spoken?” asked Odysseus in surprise.

“The Pythia has answered my question,” said the bard. “I asked what fortune should attend you on this journey, and the oracle made this reply:–

‘To home and kindred he shall safe return e’er long,With scars well-won, and greeted with triumphal song.'”

“What does it mean?” asked Odysseus.

“Just what it says,” answered the bard. “All that is now needed is that we should do our part, and fortune will surely smile upon us.”

And so, on the morrow, they bade their kind hosts farewell, and began to climb the steep pathway, which, they were told, led up and around to the rock-built halls of Autolycus. At the top of the first slope they came upon a broad table-land from the centre of which rose the peak of Parnassus towering to the skies. Around the base of this peak, huge rocks were piled, one above the other, just as they had been thrown in the days of old from the mighty hands of the Titans. On every side were clefts and chasms and deep gorges, through which flowed roaring torrents fed from the melting snows above. And in the sides of the cliffs were dark caves and narrow grottos, hollowed from the solid rock, wherein strange creatures were said to dwell.

Now and then Odysseus fancied that he saw a mountain nymph flitting among the trees, or a satyr with shaggy beard hastily hiding himself among the clefts and crags above them. They passed by the great Corycian cavern, whose huge vaulted chambers would shelter a thousand men; but they looked in vain for the nymph Corycia, who, they were told, sometimes sat within, and smiled upon passing travellers. A little farther beyond, they heard the mellow notes of a lyre, and the sound of laughter and merry-making, in a grove of evergreens, lower down the mountain-side; and Odysseus wondered if Apollo and the Muses were not there.

The path which the little company followed did not lead to the summit of the peak, but wound around its base, and then, by many a zigzag, led downward to a wooded glen through the middle of which a mountain torrent rushed. By and by the glen widened into a pleasant valley, broad and green, bounded on three sides by steep mountain walls. Here were rich pasture-lands, and a meadow, in which Odysseus saw thousands of cattle grazing. The guide told them that those were the pastures and the cattle of great Autolycus. Close to the bank of the mountain torrent,–just where it leaped from a precipice, and, forgetting its wild hurry, was changed to a quiet meadow brook,–stood the dwelling of the chief. It was large and low, and had been hewn out of the solid rock; it looked more like the entrance to a mountain cave than like the palace of a king.

Odysseus and his tutor walked boldly into the great hall; for the low doorway was open and unguarded, and the following words were roughly carved in the rock above: “Here lives Autolycus. If your heart is brave, enter.” They passed through the entrance-hall, and came to a smaller inner chamber. There they saw Autolycus seated in a chair of ivory and gold, thick-cushioned with furs; and near him sat fair Amphithea his wife, busy with her spindle and distaff. The chief was very old; his white hair fell in waves upon his great shoulders, and his broad brow was wrinkled with age: yet his frame was that of a giant, and his eyes glowed and sparkled with the fire of youth.

“Strangers,” said he kindly, “you are welcome to my halls. It is not often that men visit me in my mountain home, and old age has bound me here in my chair so that I can no longer walk abroad among my fellows. Besides this, there are those who of late speak many unkind words of me; and good men care not to be the guests of him who is called the King of Cattle Thieves.” Then seeing that his visitors still lingered at the door, he added, “I pray you, whoever you may be, fear not, but enter, and be assured of a kind welcome.”