Dorothy Mills – 1925

Mills, Dorothy. The Book of the Ancient Greeks. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1925.

CRETE AND THE CIVILIZATION OF THE EARLY AEGEAN WORLD

CHAPTER I

THE MEDITERRANEAN WORLD

To the people of the ancient world the Mediterranean was “The Sea”; they knew almost nothing of the great ocean that lay beyond the Pillars of Hercules. A few of the more daring of the Phoenician navigators had sailed out into the Atlantic, but to the ordinary sailor from the Mediterranean lands the Ocean was an unknown region, believed to be a sea of darkness, the abode of terrible monsters and a place to be avoided. And then, as they believed the world to be flat, to sail too far would be to risk falling over the edge.

But the Mediterranean was familiar to the men of the ancient world, it was their best known highway. In those ancient times, the Ocean meant separation, it cut off the known world from the mysterious unknown, but the Mediterranean did not divide; it was, on the contrary, the chief means of communication between the countries of the ancient world. For the world was then the coast {4}round the sea, and first the Phoenicians and later the Greeks sailed backwards and forwards, North and South, East and West, trading, often fighting, but always in contact with the islands and coasts. Egypt, Carthage, Athens and Rome were empires of the Mediterranean world; and the very name Mediterranean indicates its position; it was the sea in the “middle of the world.”

In the summer, the Mediterranean is almost like a lake, with its calm waters and its blue and sunny sky; but it is not always friendly and gentle. The Greeks said of it that it was “a lake when the gods are kind, and an ocean when they are spiteful,” and the sailors who crossed it had many tales of danger to tell. The coast of the Mediterranean, especially in the North, is broken by capes and great headlands, by deep gulfs and bays, and the sea, more especially that eastern part known as the Aegean Sea, is dotted with islands, and these give rise to strong currents. These currents made serious difficulties for ancient navigators, and Strabo, one of the earliest writers of Geography, in describing their troubles says that “currents have more than one way of running through a strait.” The early navigators had no maps or compass, and if they once got out of their regular course, they ran the danger of being swept along by some unknown current, or of being wrecked on some hidden rock. The result was that they preferred to sail as near the coast as was safe. This was the easier, as the Mediterranean has almost no tides, and as the early ships were small and light, landing was generally a simple {5}matter. The ships were run ashore and pulled a few feet out of the water, and then they were pushed out to sea again whenever the sailors were ready.

Adventurous spirits have always turned towards the West, and it was westwards across the Mediterranean that the civilization we have inherited slowly advanced. The early Mediterranean civilization is sometimes given the general name of Aegean, because its great centres were in the Aegean Sea and on the adjoining mainland. The largest island in the Aegean is Crete, and the form of civilization developed there is called Cretan or Minoan, from the name of one of the legendary sea-kings of Crete, whilst that which spread on the mainland is called Mycenaean from the great stronghold where dwelt the lords of Mycenae.

CHAPTER II

CRETE

The long narrow island of Crete lies at what might be called the entrance to the Aegean Sea. This sea is dotted with islands which form stepping stones from the mainland of Europe to the coast of Asia Minor. Crete turns her face to these islands and her back to Egypt, and the Egyptians, who did not travel very much themselves, called the inhabitants the “Great Men of Keftiu,” Keftiu meaning people at the back of. They were the men who dwelt beyond what was familiar to the Egyptians.

The Aegean world is a very beautiful one. The Islands rise out of the sea like jewels sparkling in the sunshine. It is a world associated with spring, of “fresh new grass and dewey lotus, and crocus and hyacinth,”[1] a land where the gods were born, one rich in legend and myth and fairy tale, and, most wonderful of all, a world where fairy tales have come true. In 1876 a telegram from an archaeologist flashed through the world, saying he had found the tomb of wide-ruling Agamemnon, King of Men and Tamer of Horses; and later on, in Crete, traces were {7}found of the Labyrinth where Theseus killed the Minotaur. The spade of the archaeologist brought these things into the light, and a world which had hitherto seemed dim and shadowy and unreal suddenly came out into the sunshine.

[1] Iliad, XIV.

There is a land called Crete in the midst of the wine-dark sea, a fair land and a rich, begirt with water, and therein are many men innumerable and ninety cities.[2]

[2] Odyssey, XIX.

Legend tells us that it was in this land that Zeus was born, and that a nymph fed him in a cave with honey and goat’s milk. Here, too, in the same cave was he wedded and from this marriage came Minos, the legendary Hero-King of Crete. The name Minos is probably a title, like Pharaoh or Caesar, and this Minos, descendant of Zeus, is said to have become a great Sea-King and Tyrant. He ruled over the whole of the Aegean, and even demanded tribute from cities like Athens. But Theseus, helped by the King’s daughter Ariadne, slew the Minotaur, the monster who devoured the Athenian youths and maidens, and so defeated the vengeance of the King. This Minos fully realized the importance of sea-power in the Aegean. Thucydides, the Greek historian, tells us that he was the first ruler who possessed a navy, and that in order to protect his increasing wealth, he did all that was in his power to clear the sea of pirates. Piracy was a recognized {8}trade in those days, and when strange sailors landed anywhere, the inhabitants would come down to the shore to meet them with these words: “Strangers, who are ye? Whence sail ye over the wet ways? On some trading enterprise or at adventure do ye rove, even as sea-robbers over the brine?”[3

[3 Odyssey, III.] Minos himself may have been a great pirate who subdued all the others and made them subject to him, but whether this were so or not, he was evidently not only a great sea-king; legend and tradition speak of him as a great Cretan lawgiver. Every year he was supposed to retire for a space to the Cave of Zeus, where the Father of Gods and Men gave him laws for his land. It is because of the great mark left by Minos on the Aegean world, that the civilization developed there is so often called Minoan, thus keeping alive for ever the name of its traditional founder.

The Labyrinth in which the Minotaur was slain was built by Daedalus, an Athenian. He was a very skilful artificer, and legend says that it was he who first thought of putting masts into ships and attaching sails to them. But he was jealous of the skill of his nephew and killed him, and so was forced to flee from Athens, and he came to Knossos where was the palace of Minos. There he made the Labyrinth with its mysterious thousand paths, and he is also said to have “wrought in broad Knossos a dancing-ground for fair-haired Ariadne.”[4]

[4 – Iliad, XVIII]

But Daedalus lost the favour of Minos, who imprisoned him with his son Icarus. The cunning of {9}the craftsman, however, did not desert him, and Daedalus skilfully made wings for them both and fastened them to their shoulders with wax, so that they flew away from their prison out of reach of the King’s wrath. Icarus flew too near the sun, and the wax melted, and he fell into the sea and was drowned; but Daedalus, we are told, reached Sicily in safety.

The Athenians believed that Theseus and Minos had really existed, for the ship in which, according to tradition, Theseus made his voyage was preserved in Athens with great care until at least the beginning of the third century B.C. This ship went from Athens to Delos every year with special sacrifices, and one of these voyages became celebrated. Socrates, the philosopher, had been condemned to death, but the execution of the sentence was delayed for thirty days, because this ship was away, and so great was the reverence in which this voyage was held that no condemned man could be put to death during its absence.[5] It was held that such an act would bring impurity on the city.

II. THE PALACES OF CRETE

The first traces of history in Crete take us back to about 2500 B.C. but it was not till about a thousand years later that Crete was at the height of her prosperity and enjoying her Golden Age. Life in Crete at this time must have been happy. The Cretans built their cities without towers or fortifications; they were a mighty sea power, but they lived more {10}for peace and work than for military or naval adventures, and having attained the overlordship of the Aegean, they devoted themselves to trade, industries and art.

The Cretans learnt a great deal from Egypt, but they never became dependent upon her as did the Phoenicians, that other seafaring race in the Mediterranean. They dwelt secure in their island kingdom, taking what they wanted from the civilization they saw in the Nile Valley; but instead of copying this, they developed and transformed it in accordance with their own spirit and independence.

The chief city in Crete was Knossos, and the great palace there is almost like a town. It is built round a large central court, out of which open chambers, halls and corridors. This court was evidently the centre of the life of the palace. The west wing was probably devoted to business and it was here that strangers were received. In the audience chamber was found a simple and austere seat, yet one which seizes upon the imagination, for it was said to be the seat of Minos, and is the oldest known royal throne in the world.

In the east wing lived the artisans who were employed in decorating and working on the building, for everything required in the palace was made on the spot. The walls of all the rooms were finished with smooth plaster and then painted; originally that the paint might serve as a protection, but later because the beauty-loving Cretans liked their walls to be covered with what must have been a joy to look at, and which reminded them at every turn of {11}the world of nature in which they took such a keen delight. The frescoes are now faded, but traces of river-scenes and water, of reeds and rushes and of waving grasses, of lilies and the crocus, of birds with brilliant plumage, of flying fish and the foaming sea can still be distinguished.

The furniture has all perished, but many household utensils have been found which show that life was by no means primitive, and the palaces were evidently built and lived in by people who understood comfort. In some ways they are quite modern, especially in the excellent drainage system they possessed. These Cretan palaces were warmer and more full of life than those in Assyria, and they were dwelt in by a people who were young and vigorous and artistic, and who understood the joy of the artist in creating beauty.

Near the palace was the so-called theatre. The steps are so shallow that they could not have made comfortable seats, and the space for performances was too small to have been used for bull-fights, which were the chief public entertainments. The place was probably used for dancing, and it may have been that very dancing ground wrought for Ariadne.[6]

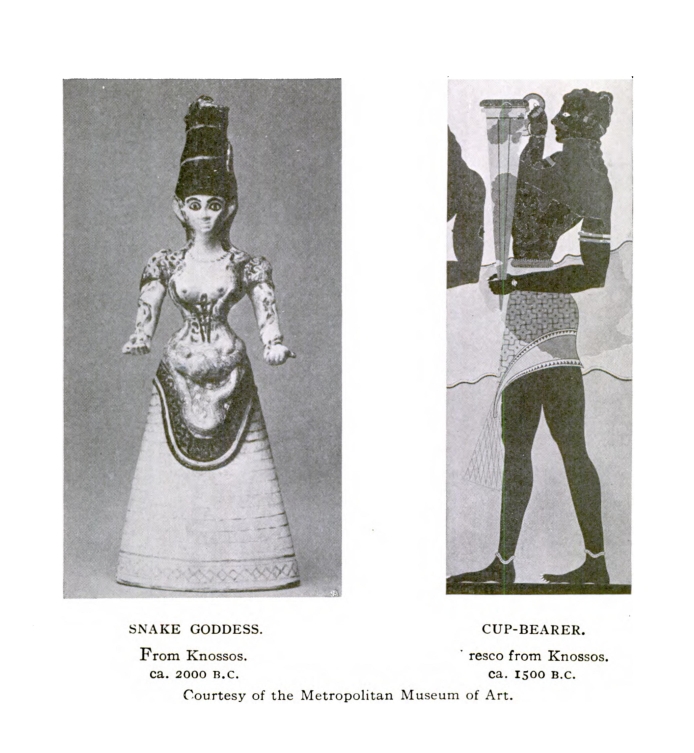

III. DRESS

The dress of the Cretan women was surprisingly modern. The frescoes on the walls, as well as small porcelain statuettes that have been found, give us {12}a very clear idea of how the people dressed. The women had small waists and their dresses had short sleeves, with the bodice laced in front, and wide flounced skirts often richly embroidered. Yellow, purple and blue seem to have been the favourite colours. They wore shoes with heels and sometimes sandals. Their hair was elaborately arranged in knots, side-curls and braids, and their hats were amazingly modern.

The men were not modern-looking. Their only garment was a short kilt, which was often ornamented with designs in colours, and like the women, they had an elaborate method of hair-dressing. In general appearance the men were bronzed, slender and agile-looking.

SNAKE GODDESS. From Knossos. ca. 2000 B.C.

CUP-BEARER. Fresco from Knossos, ca. 1500 B.C.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.’

“Snake Goddess.” Khan Academy, www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/aegean-art1/minoan/a/snake-goddess. Accessed 5 Sept. 2022.

Some of the frescoes are so lifelike that as they were brought to light during the excavations, it almost seemed as if the spirits of the long-dead Cretans were returning to the earth. The workmen felt the spell, and Sir Arthur Evans, who excavated Knossos, has described the scene as the painting of a young Cretan was found:

The colours were almost as brilliant as when laid down over three thousand years before. For the first time the true portraiture of a man of this mysterious Mycenaean race rises before us. There was something very impressive in this vision of brilliant youth and of male beauty, recalled after so long an interval to our upper air from what had been till yesterday a forgotten world. Even our untutored Cretan workmen felt the spell and fascination.

They, indeed, regarded the discovery of such a painting {13}in the bosom of the earth as nothing less than marvellous, and saw in it the “ikon” of a saint! The removal of the fresco required a delicate and laborious process of under-plastering, which necessitated its being watched at night, and one of the most trustworthy of our gang was told off for the purpose. Somehow or other he fell asleep, but the wrathful saint appeared to him in a dream. Waking with a start he was conscious of a mysterious presence; the animals round began to low and neigh, and there were visions about; in summing up his experiences the next morning, “The whole place spooks!” he said.[7]

Crete seems to have had more than the other earlier civilizations of what today is called society. The women were not secluded but mixed freely at court and in all social functions, and life seems to have been joyous and free from care.

IV. RELIGION AND LITERATURE

(a) Religion

We know almost nothing of the Cretan religion. There were no idols or images for worship and no temples. The people worshipped in their houses, and every house seems to have had a room set apart for this purpose with its shrine and altar; pillars were one of the distinguishing marks of these shrines. The chief goddess was the Mother Earth, the Source of Life, a spirit who had a good and kindly character. Sometimes she was called the Lady of the Wild Creatures, and bulls were sacrificed in her honour. Scenes representing such sacrifices are to be found {14}on engraved gems, and the horns of the bull are frequently found set up on altars and shrines. This Earth Goddess was Goddess both of the Air and of the Underworld: when she appears as the Goddess of the Air, she has doves as her symbol; when she appears as the Goddess of the Underworld, she has snakes.

Another sacred symbol found in connection with shrines and altars is the Axe and often a Double Axe. This seems to have been looked upon as a divine symbol representing power, for it is the axe which transforms all kinds of material into useful articles and by means of man’s toil it supplies much of what man needs. Ships could not be built without an axe, and as it was the ship which gave Crete power in the Aegean, the axe came to be looked upon as symbolizing this spirit.

These early Aegean people did not feel the need of any temples. When they worshipped in what they thought was the dwelling place of the gods, they chose lonely places, remote hill-tops or caverns or the depths of a great forest. They selected for this worship some place that was apart from the daily human life and one that had never been touched by the hand of man, for they felt that it was such places that the god would choose for his dwelling. From such spots developed the idea of a temple; it was to be a building enclosed and shut out from the world, just as the forest grove had been surrounded by trees, a place apart from the life of man.

It was the custom in these early times for people to bring to the god or goddess offerings of that which {15}was most valuable to them. The best of the flock, the finest fruit, the largest fish, the most beautiful vase, were all looked upon as suitable offerings. But many people could not afford to part with the best of the first-fruits of their toil, and so it became the custom to have little images made of the animal or other offering they wished to make, and these were placed in the shrine. Such images are called votive offerings, and they are a source of rich material out of which the archaeologist has been able to rebuild parts of ancient life.

One reason why it has been so difficult to know much about the Cretan religion is because the writing has not yet been deciphered. Over sixty different signs have been recognized, but no key has yet been found by means of which the writing can be read. In the palace at Knossos a great library was found, consisting of about two thousand clay tablets. These had evidently been placed in wooden chests, carefully sealed, but at the destruction of Knossos the fire destroyed the chests, though it helped to preserve the clay records. Some of these were over-charred and so became brittle and broke, but there are still quantities awaiting decipherment. The writing does not look as if it represented literature, but more as if it were devoted to lists and records. It seems strange that people dwelling in a land so rich in legend and story, and possessed of the art of writing, should not have left a literature. But in those days the songs of minstrels preserved the {16}hero-tales in a form that was then considered permanent, for the minstrel gathered his tales together and handed them down to his successor by word of mouth in a way that we, with our careless memories, deem marvellous. This was actually considered a safer way of preserving the tales and poems than trusting them to the written form. Be that as it may, however, the writing that is there still awaits the finding of a key. But in spite of these difficulties, life in Crete can be partially reconstructed, and so it will be possible for us to spend a day in the palace of ancient Knossos.

V. A DAY IN CRETE

It is early dawn about the year 1500 B.C. The great palace of Knossos lies quiet and still, for the inhabitants have not yet begun to stir. When they are aroused, the noise will be like the bustle of a town, for everything used in the palace is made there, from the bronze weapons used by the King when he goes out hunting to the great clay vessels in which not only wine and oil, but also other articles of food are kept. The palace is guarded by sentries, and the first person to come out of it in the morning is an officer who goes the rounds and receives the reports of the night’s watch from each sentry. He then goes into the royal storerooms, where rows of large vessels stand against the wall, and he inspects them to make sure that no robbery has taken place and also that there are no leaks and no wine or oil lost.

By this time the sun is up and the workmen are going to the palace workshops, where some are at work on pottery, others are weaving, and others working with metals. Some of the potters are fashioning beautiful vases, the younger workmen copying the well-known patterns, the more experienced thinking of new forms, but all of them handing over the finished vessel to the artist who paints beautiful designs on them. The weavers have been very busy of late, for today is the birthday of the Princess, and great festivities are to be held in her honour, and not only the Princess but the Queen and her maidens and all the ladies of the court need new and dainty robes for the functions of the day. The goldsmiths also have been hard at work, for the King has ordered exquisite jewellery as a gift for his daughter. All these workmen are now putting the finishing touches to their work, and in a few hours they will take it to the officials who will see that it is delivered to the royal apartments.

Soon all is bustling in the kitchens, for later in the day a great banquet will be held. Farmers from the country-side come with the best of their flocks, with delicious fruits and honey; fishermen from the shore have been out early and have caught fine fish. Nearly every one who comes has brought some special dainty as a particular offering for the Princess, for she is much beloved in Knossos and in all the country round about.

The morning is spent in preparation for the festivities of the afternoon. The Princess is arrayed by her maidens in her new and beautiful robes; her hair {18}is elaborately arranged, a long and tiresome process, but the time is enlivened by the merry talk of the maidens who give to their young mistress all the gossip of the palace. At length she is ready, and she goes to the great audience chamber, where the King her father presents to her the shining ornaments he has had made for this day. Then, sitting between her parents, she receives the good wishes of the courtiers, all of whom have brought her rich gifts.

This reception is followed by an exhibition of boxing and bull-fighting, favourite amusements of the Cretan youths; but the great excitement of the day is the wild boar hunt which follows. All the youths and younger men take part, and each hopes that he may specially distinguish himself in order that on his return he may have some trophy to present to the Princess, and that she will reward him by giving him her hand in the dance that evening.

While the young men are all away at the hunt, the Princess sits with her parents in the great hall or wanders with her maidens in the gardens. Great excitement prevails when the hunters return. On arriving, they hasten to the bath and anoint themselves with oil and curl their long hair and make themselves ready for the dance. When all are ready they go out to that

dancing place, which Daedalus had wrought in broad Knossos for Ariadne of the lovely tresses. There were youths dancing and maidens of costly wooing, their hands on one another’s wrists. Fine linen the maidens had on, and the youths well-woven doublets faintly {19}glistening with oil. Fair wreaths had the maidens, and the youths daggers of gold hanging from silver baldrics. And now they would run around with deft feet exceeding lightly, as when a potter sitting by his wheel maketh trial of it whether it run; and now anon they would run in lines to meet one another. And a great company stood around the lovely dance in joy; and among them a divine minstrel was making music on his lyre, and through the midst of them, as he began his strain, two tumblers whirled.[8]

The dance over, the feasting and banqueting begins. The Queen and the Princess with their maidens retire early to their own apartments, but the merrymaking goes on in the hall, where tales of the day’s hunt are told, and old tales of other adventures are recalled by the old men, until weariness overcomes them. Then the Queen sends her handmaids who “set out bedsteads beneath the gallery, and cast fair purple blankets over them, and spread coverlets above, and thereon lay thick mantles to be a clothing over all. Then they go from the hall with torch in hand.” So the youths and men lie down and go to sleep, and after the excitements of the day “it seemed to them that rest was wonderful.”[9]

VI. THE DESTROYERS

After the glory of the Golden Age of Crete came destruction. Some tremendous disaster broke for ever the power of the Sea-Kings. We do not know {20}what happened, beyond the fact that Knossos was burned, but from our knowledge of the life of the time and the methods of warfare, we can make a picture of what probably took place. There may have been some terrible sea fight, in which the fleet was worsted and driven back upon the shore. Then the conquerors would march upon the town and besiege it. The inhabitants, knowing that all was at stake, would defend it to the last with the most savage fury, cheered on by the women, who knew that if the city was taken there would be no hope for them. Their husbands and sons would be slain, the city utterly destroyed by fire and themselves taken captive. This is what happened at Knossos. We know the fate of the city, but nothing of the conquerors. Egyptian records of this time say that “the isles were restless, disturbed among themselves,” but that is all we know.

The invaders, whoever they were, and from whereever they came, do not seem to have been men of a highly civilized type, for they left untouched many works of real art, and carried off only such articles as could be turned into material wealth. These were the things they evidently valued, and the degree of civilization to which nations or individuals have attained, can usually be measured by the comparative values they put on things.

And so Knossos fell, and she tasted of “the woes that come on men whose city is taken: the warriors are slain, and the city is wasted of fire, and the children and women are led captive of strangers.”[10]

The old Knossos was never rebuilt, though another city grew up in the neighbourhood. The site of the old palace became more and more desolate, until at length the ruins were completely hidden under a covering of earth, and the ancient power and glory of Crete became only a tradition. And so it remained for long centuries, until archaeologists, discovering what lay beneath those dreary-looking mounds, recalled for us that spring-time of the world.

[1] Iliad, XIV.

[2] Odyssey, XIX.

[3]Odyssey, III.

[4] Iliad, XVIII.

[5] See p. 374.

[6] Important excavations in other parts of Crete have been carried on by Mr. and Mrs. Hawes. (See Bibliography, p. 410).

[7] Sir Arthur Evans: in the Monthly Review, March, 1901.

[8] Iliad, XVIII.

[9] Odyssey, VII.

[10] Iliad, IX.

CHAPTER III

THE MAINLAND

I. TROY AND THE FIRST DISCOVERIES

An ancient tradition told the story of how Helen, the beautiful wife of Menelaus King of Sparta, had been carried off by Paris, son of the King of Troy, and of how the Greeks collected a mighty army under Agamemnon, King of Argos and his brother Menelaus and sailed to Troy to bring back the lost Helen. For ten years they besieged Troy, during which time they had many adventures and many hero-deeds were performed. Glorious Hector of the glancing helm was slain by Achilles fleet of foot, and the gods and goddesses themselves came down from high Olympus and took sides, some helping the Trojans and some the Greeks. At length Troy was taken and the Greek heroes returned home, but their homeward journey was fraught with danger and they experienced many hardships. The wise Odysseus, especially, went through many strange adventures before he reached Greece again. All these tales were put together by the Greek poet Homer, and may be read in the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Until the beginning of the nineteenth century no {23}one had seriously thought that there was any truth in these tales. But in 1822 a boy was born in Germany who was to make the most extraordinary discoveries about these lands of legend.

Henry Schliemann was the son of a German pastor who was well versed in all these ancient legends, and as he grew up, he learned all about Troy and the old Greek tales. He lived in a romantic neighbourhood. Behind his father’s garden was a pool, from which every midnight a maiden was said to rise, holding a silver bowl in her hand, and there were similar tales connected with the neighbouring hills and forests. But there was not much money to educate the young Schliemann, and when he was fourteen years old he was taken as errand boy by a country grocer. This was not perhaps the occupation a romantic-minded youth would have chosen, but there was no help for it. One evening, there came into the shop a man, who after sitting down and asking for some refreshment, suddenly began to recite Greek poetry. The errand boy stopped his work to listen, and long afterwards he described the effect this poetry had on him:

That evening he recited to us about a hundred lines of the poet (Homer), observing the rhythmic cadence of the verses. Although I did not understand a syllable, the melodious sound of the words made a deep impression upon me, and I wept bitter tears over my unhappy fate. Three times over did I get him to repeat to me those divine verses, rewarding his trouble with three glasses of whiskey, which I bought with the few pence that made up my whole wealth. From that moment I never {24}ceased to pray God that by His grace I might yet have the happiness of learning Greek.

A few years later, Schliemann was taken as errand boy in a business house in Amsterdam, and he had to run on all kinds of errands and carry letters to and from the post. He says of this time:

I never went on my errands, even in the rain, without having my book in hand and learning something by heart. I never waited at the post-office without reading or repeating a passage in my mind.

Schliemann got on well and the time came when he was able to found a business of his own. Now at last he had time to learn Greek, and he read everything written by or about the ancient Greeks on which he could lay his hands. And then came the time to which he had been looking forward all his life. He was able to free himself from his business and to sail for the Greek lands.

Schliemann believed that the tales of Troy were founded on true historic facts, but everybody laughed at this opinion, and he was often ridiculed for holding it so firmly. Now, however, he was to prove himself victorious, for he went to the place where he believed Troy had once stood and began to dig. His expectations were more than realized, for he found six cities, one of which was later conclusively proved to be the Troy of Homer! Homer had written about what was really true, and though legends and myths had been woven into his poem, the main events had really taken place, and a civilization {25}which up to that time had, as it was thought, never existed, suddenly came out into the record of history.

II. MYCENAE AND TIRYNS

All these discoveries sent a thrill of excitement through the world, and of course at first many mistakes were made. Because Troy was found to have really existed, everything found there was immediately connected with the Trojan heroes of the Iliad, and some things which were obviously legendary were treated as facts. Schliemann himself was not entirely free from these first exaggerations, but encouraged by what he had already discovered, he determined to find still more.

Now Pausanias, an ancient Greek traveller, had written a book about his travels, and one of the places he had visited was Mycenae on the mainland of Greece. Here, he said, he had seen the tomb of Agamemnon, who on his return from Troy had been murdered by his wife, Clytemnestra, and hastily buried. Up to the time of Schliemann no one had seriously believed that there had ever been such a person as Agamemnon, but the spirit of discovery was in the air, and what might not still be found! Schliemann determined that having proved that Troy had once existed, he would find truth in still more legends, and he went to Mycenae and began to excavate. The early Greeks had not the same beliefs about the future life that the Egyptians had, but they did believe that death meant removing the dwelling-place on earth to one beneath the {26}earth, and so the early Greek tomb was built in much the same shape as the earthly house. These Greeks did not allow man to go naked and alone into the other world; they gave to the departed to take with him all that was best and finest of his earthly possessions. They filled the tomb with everything that could add to his comfort, and if he were a king or great chief, he would be surrounded by things which would mark him out from other men and point to his great position. This being so, Schliemann thought that a king’s tomb would be easily recognized, and he opened what he thought was probably the burial place of Agamemnon. What he saw swept him off his feet with excitement! Before doing anything else he sent a telegram to the King of Greece, which was speedily published throughout the world. The telegram said: “With great joy I announce to Your Majesty that I have found the tomb of Agamemnon!”

The sensation created by this news was tremendous. That it was really the tomb of the wide-ruling King of Argos was perhaps uncertain, but it was undoubtedly the tomb of a great lord who had lived at the same time, and at his death had been buried in barbaric magnificence. Diadems, pendants, necklaces, ornaments of all kinds, goblets, plates, vases, all of pure gold were piled high in confusion in the tomb, and close by were other tombs also filled with untold treasure. In one grave alone Schliemann counted 870 objects made of the purest gold. This was only the beginning of excavations at Mycenae. Later on, a great palace was uncovered, and other {27}work at Tiryns, nearer the sea, showed that another palace had existed there.

These buildings were very unlike the palace at Knossos; the latter had no fortifications, but these were strongly fortified. They had great walls, so mighty that in ancient times the Greeks thought the walls of Tiryns had been built by demons, and Pausanias considered them even more wonderful than the Pyramids. The fortress palace of Mycenae was entered by the gate of the Lionesses, which was reached by a rather narrow road, along which only seven men could march abreast. This seems a rather mean approach to so splendid a palace, but such narrow approaches were necessary in those war-like times, for they made it more difficult for an enemy to approach the gates.

Mycenae and Tiryns are the best known today of the ancient fortress-palaces on the mainland of Greece, but at the time when they were built there were many others. The great lords frequently chose the hill-tops for their dwellings, for the sake of better security and for the protection they could then in their turn afford the surrounding country people in times of danger. Most of these fortress-palaces were in the neighbourhood of the coast, for no true Greek was ever quite happy unless he were within easy reach and sight of the sea.

III. LIFE IN THE HOMERIC AGE

The Homeric Age was the age of the great hero-kings and chiefs. Most of these were supposed to {28}be descended from the gods, and they shine through the mists of the early days in Greece as splendid, gorgeous figures. Heaven was nearer to the earth in those days, and the gods came down from Olympus and mixed familiarly with man. Life was very different in this heroic age from the life of historic Greece, and it is evident from the excavations and discoveries that have been made, that it was a civilization with distinct characteristics of its own which preceded what is known as the Greece of history. It was an age when the strong man ruled by the might of his own strong arm, and piracy was quite common. Manners and customs were very primitive and simple, yet they were combined with great material splendour. Women held a high position in this society and they wore most gorgeous clothes. A Mycenaean lady, arrayed in her best, would wear a dress of soft wool exquisitely dyed or of soft shining linen, and she would glitter with golden ornaments: a diadem of gold on her head, gold pins in her hair, gold bands round her throat, gold bracelets on her arms, and her hands covered with rings. Schliemann says that the women he found in one of the tombs he opened were “literally laden with jewellery.”

The fortress-palaces were the chief houses and the huts of the dependents of the king or chief would be crowded round them, but these huts have, of course, disappeared. The palaces themselves were strongly built, with courtyards and chambers opening from them. “There is building beyond building, and the court of the house is cunningly wrought with a wall {29}and battlements, and well-fenced are the folding doors; no man may hold it in disdain.”[1] Excavations have proved that the Homeric palaces did indeed exist: and well fortified though they were, their gardens and vineyards and fountains must have made of them very pleasant dwelling-places.

There was a gleam as it were of sun or moon through the high-roofed hall of great-hearted Alcinous. Brazen were the walls which ran this way and that from the threshold to the inmost chamber, and round them was a frieze of blue, and golden were the doors that closed in the good house. Silver were the door-posts that were set on the brazen threshold, and silver the lintel thereupon, and the hook of the door was of gold. And on either side stood golden hounds and silver, which Hephaestus had wrought by his cunning, to guard the palace of great-hearted Alcinous, being free from death and age all their days. And within were seats arrayed against the wall this way and that, from the threshold even to the inmost chamber, and thereon were spread light coverings finely woven, the handiwork of women. There the chieftains were wont to sit eating and drinking for they had continual store. Yea, and there were youths fashioned in gold, standing on firm-set bases, with flaming torches in their hands, giving light through the night to the feasters in the palace. And he had fifty handmaids in the house, and some grind the yellow grain on the mill-stone, and others weave webs and turn the yarn as they sit, restless as the leaves of the tall poplar tree: and the soft olive oil drops off that linen, so closely is it woven. And without the courtyard hard by the door is a great garden, and a hedge runs round on either {30}side. And there grow tall trees blossoming, pear-trees and pomegranates, and apple-trees with bright fruit, and sweet figs, and olives in their bloom. The fruit of these trees never perisheth, neither faileth, winter nor summer, enduring through all the year. Evermore the West Wind blowing brings some fruits to birth and ripens others. Pear upon pear waxes old, and apple on apple, yea and cluster ripens upon cluster of the grape, and fig upon fig. There too hath he a fruitful vineyard planted, whereof the one part is being daily dried by the heat, a sunny spot on level ground, while other grapes men are gathering, and yet others they are treading in the wine-press. In the foremost row are unripe grapes that cast the blossom, and others there be that are growing black to vintaging. There too, skirting the furthest line, are all manner of garden beds, planted trimly, that are perpetually fresh, and therein are two fountains of water, whereof one scatters his streams all about the garden, and the other runs over against it beneath the threshold of the courtyard and issues by the lofty house, and thence did the townsfolk draw water. These were the splendid gifts of the gods in the palace of Alcinous.[2]

A blue frieze just like the one described above has been found both at Mycenae and Tiryns.

The furniture in these houses was very splendid. We read of well-wrought chairs, of goodly carven chairs and of chairs inlaid with ivory and silver; of inlaid seats and polished tables; of jointed bedsteads and of a fair bedstead with inlaid work of gold and silver and ivory; of close-fitted, folding doors and of doors with silver handles; and of rugs of soft wool. Rich and varied were the ornaments and vessels {31}used: goodly golden ewers and silver basins, two-handled cups, silver baskets and tripods, mixing bowls of flowered work all of silver and one that was beautifully wrought all of silver and the lips thereof finished with gold. The most famous cup of all was that of the clear-voiced orator Nestor; this had four handles on which were golden doves feeding and it stood two feet from the ground. Very skilful was all the work done in metal at this time, and the warriors went out arrayed in flashing bronze, bearing staves studded with golden nails, bronze-headed spears and silver-studded swords, their greaves were fastened with silver clasps, they wore bronze-bound helmets, glittering girdles and belts with golden buckles. Only a god could have fashioned a wondrous shield such as Achilles bore, on which were depicted scenes from the life of the time (the description of it can be read in the Iliad), but the tombs at Mycenae and elsewhere have yielded weapons and treasures very similar to those used by the heroes in Homer.

IV. THE GREEK MIGRATIONS

It was more than a thousand years after the Pyramids had been built that Crete reached her Golden Age. When Knossos was destroyed, the centres of civilization on the mainland, such as Mycenae and Tiryns, became of greater importance, and life was lived as Homer has described it. All this was the Greece of the Heroic Age, the Greece to which the Greeks of the later historical times {32}looked back as to something that lay far behind them.

Nearly two thousand years ago the site of Mycenae was just as it had remained until the excavations of Schliemann, and in the second century A.D. a Greek poet sang of Mycenae:

The cities of the hero-age thine eyes may seek in vain,

Save where some wrecks of ruin still break the level plain.

So once I saw Mycenae, the ill-starred, a barren height

Too bleak for goats to pasture—the goat-herds point the site.

And as I passed a greybeard said: “Here used to stand of old

A city built by giants and passing rich in gold.”[3]

Even to the Greeks of historical times there was a great gap between the return of the heroes from Troy and the beginnings of their own historic Greece. That gap has not yet been entirely filled up; it is even now a more shadowy and misty period to us than the Age of the Heroes, but it was during these mysterious centuries that there were wanderings among the peoples, that restlessness and disturbance spoken of by the Egyptians. It was a dark period in the history of Greece. Wandering tribes, tall and fair men, came from out the forests of the north, over the mountains and through the passes into Greece. Others came from the East. Some again came by sea, driven out from their island homes by invaders. There was fighting and slaying and {33}taking of prisoners. The old civilization was broken down, but slowly something new arose in its place. There were enemies on all sides, but gradually those who were left of the conquered made terms with the conquerors; they abandoned their old language and adopted that of the newcomers, and they dwelt together, and were known as Greeks. The older civilizations had done their work and had perished. The time had come for the mind of man to make greater advances than he had ever before dreamed of, and in the land of Greece this period begins with the coming of the Greeks.

[1] Odyssey, XVII.

[2] Odyssey, VII.

[3] Alpheus, translated by Sir Rennell Rodd in Love, Worship and Death.

THE GREEKS

CHAPTER I

THE LAND OF GREECE

The land to which people belong always helps to form their character and to influence their history, and the land of Greece, its mountains and plains, its sea and sky, was of great importance in making the Greeks what they were. The map shows us three parts of Greece: Northern Greece, a rugged mountainous land; then Central Greece with a fertile plain running down to more mountains; and then, across a narrow sea, the peninsula known as the Peloponnesus. One striking feature of the whole country is the nearness of every part of it to the sea. The coast is deeply indented with gulfs and bays, and the neighbouring sea is dotted with islands. It is a land of sea and mountains.

The soil is not rich. About one-third of the country is mountainous and unproductive and consists of rock. Forests are found in the lower lands, but they are not like our forests; the trees are smaller and the sun penetrates even the thickest places. The trees most often found are the laurel, the oleander and the myrtle. The forests were thicker in ancient times; {38}they are much thinner now owing to the carelessness of peasants who, without thinking of the consequences, have wastefully cut down the trees.

The land used by the Greeks for pasture was that which was not rich enough for cultivation. Goats and sheep and pigs roamed over this land, and the bees made honey there. In ancient times there was no sugar and honey was a necessary article of food.

The cultivated land lay in the plains. The mountains of Greece do not form long valleys, but they enclose plains, and it was here that the Greeks cultivated their corn and wine and oil, and that their cities grew up separated from each other by the mountains. Corn, wine and oil were absolutely necessary for life in the Mediterranean world. Every Greek city tried to produce enough corn, chiefly wheat and barley, for its inhabitants, for the difficulties and sometimes dangers were great when a city was not self-sufficing. Wine, too, was necessary, for the Greeks, though they were a temperate nation, could not do without it. Oil was even more important, for it was used for cleansing purposes, for food and for lighting. Even to-day the Greeks use but little butter, and where we eat bread and butter, they use bread and olives or bread and goat’s cheese. The olive is cultivated all over Greece, but especially in Attica, where it was regarded as the gift of Athena herself. It was looking across the sea to Attica that—

In Salamis, filled with the foaming

Of billows and murmur of bees,

{39}Old Telamon stayed from his roaming,

Long ago, on a throne of the seas;

Looking out on the hills olive-laden,

Enchanted, where first from the earth

The grey-gleaming fruit of the Maiden

Athena had birth.[1]

The olive is not a large tree and its chief beauty is in the shimmer of the leaves which glisten a silvery-grey in the sunshine. Olive trees take a long time to mature. They do not yield a full crop for sixteen years or more, and they are nearly fifty years old before they reach their fullest maturity. It is no wonder that the olive is a symbol of peace.

Herodotus, the earliest of the Greek historians, wrote that “it was the lot of Hellas to have its seasons far more fairly tempered than other lands.” The Mediterranean is a borderland, midway between the tropics and the colder North. In summer the cool winds from the North blow upon Greece making the climate pleasant, but in winter they blow from every quarter, and according to the poet Hesiod were “a great trouble to mortals.” Greek life was a summer life, and the ancient Greeks lived almost entirely out-of-doors: sailing over the sea, attending to all their affairs in the open air, from the shepherd watching his flock on the mountain side to the philosopher discussing politics in the market place. But the Greeks were a hardy race, and though the winter life must have been chilly and uncomfortable, life went on just the same, until the {40}warm spring sunshine made them forget the winter cold.

What kind of people were made by these surroundings and what was their spirit?

The hardy mountain life developed a free and independent spirit, and as the mountains cut off the dwellers in the different plains from each other, separate city-states were formed, each with its own laws and government. This separation of communities was a source of weakness to the country as a whole, but it developed the spirit of freedom and independence in the city dweller as well as in the mountaineer. As all parts of Greece were within easy reach of the sea, the Greeks naturally became sailors. They loved the sea and were at home upon it, and this sea-faring life developed the same spirit of freedom and independence.

The mild climate relieved the Greeks of many cares which come to those who live in harsher lands, but the atmosphere was clear and bracing, which stimulated clear thinking. The Greeks were the first great thinkers in the world; they were possessed of a passion for knowing the truth about all things in heaven and earth, and few people have sought truth with greater courage and clearness of mind than the Greeks.

The poor soil of their land made it necessary for them to work hard and to form habits of thrift and economy. It was not a soil that made them rich and so they developed a spirit of self-control and moderation, and learned how to combine simple living with high thinking to a greater degree than {41}any other nation has ever done. But if their soil was poor, they had all round them the exquisite beauty of the mountains, sea and sky, surroundings from which they learned to love beauty in a way that has never been excelled, if, indeed, it has ever been equalled.

The spirit of a nation expresses itself and its history is recorded in various ways: in the social relations of the people both with each other and with other nations, and this is called its political history; in its language which expresses itself in its literature; and in its building, which is its architecture. The Greek people were lovers of freedom, truth, self-control and beauty. It is in their political history, their literature and their architecture that we shall see some of the outward and visible signs of the spirit that inspired them, and the land of Greece is the setting in which they played their part in the history of civilization.

[1] Euripides: The Trojan Women, translated by Gilbert Murray.

CHAPTER II

GREEK RELIGION AND THE ORACLES

The city-dwellers in Greece lived in the plains separated from their neighbours by mountains, and this caused the development of a large number of separate communities, quite independent of each other, each having its own laws and government, but there were three things which all Greeks had in common wherever they lived: they spoke the same language, they believed in the same gods, and they celebrated together as Greeks their great national games.

The Greeks called themselves Hellenes and their land Hellas. Like the Hebrews and the Babylonians, they believed that there had been a time when men had grown so wicked that the gods determined to destroy the old race of man and to create a new one. A terrible flood overwhelmed the earth, until nothing of it was left visible but the top of Mount Parnassus, and here, the old legend tells us, a refuge was found by two people, Deucalion and his wife Pyrrha, who alone had been saved on account of their righteous lives. Slowly the waters abated, until the earth was once more dry and habitable, but Deucalion and Pyrrha were alone and did not {43}know what they should do. So they prayed to the gods and received as an answer to their prayer the strange command: “Depart, and cast behind you the bones of your mother.” At first they could not understand what was meant, but at length Deucalion thought of an explanation. He said to Pyrrha: “The earth is the great mother of all; the stones are her bones, and perhaps it is these we must cast behind us.” So they took up the stones that were lying about and cast them behind them, and as they did so a strange thing happened! The stones thrown by Deucalion became men, and those thrown by Pyrrha became women, and this race of men peopled the land of Greece anew. The son of Deucalion and Pyrrha was called Hellen, and as the Greeks looked upon him as the legendary founder of their race, they called themselves and their land by his name.

These earliest Greeks had very strange ideas as to the shape of the world. They thought it was flat and circular, and that Greece lay in the very middle of it, with Mount Olympus, or as some maintained, Delphi, as the central point of the whole world. This world was believed to be cut in two by the Sea and to be entirely surrounded by the River Ocean, from which the Sea and all the rivers and lakes on the earth received their waters.

In the north of this world, were supposed to live the Hyperboreans. They were the people who lived beyond the North winds, whose home was in the caverns in the mountains to the North of Greece. The Hyperboreans were a happy race of beings who {44}knew neither disease nor old age, and who, living in a land of everlasting spring, were free from all toil and labour.

Far away in the south, on the banks of the River Ocean, lived another happy people, the Aethiopians. They were so happy and led such blissful lives, that the gods used sometimes to leave their home in Olympus and go and join the Aethiopians in their feasts and banquets.

On the western edge of the earth and close to the River Ocean were the Elysian Fields, sometimes called the Fortunate Fields and the Isles of the Blessed. It was to this blissful place that mortals who were specially loved by the gods were transported without first tasting of death, and there they lived forever, set free from all the sorrows and sufferings of earth, it was a land—

Where falls not hail, or rain, or any snow,

Nor ever wind blows loudly; but it lies

Deep-meadow’d, happy——.

The Sun and the Moon and the Rosy-fingered Dawn were thought of as gods who rose out of the River Ocean and drove in their chariots through the air, giving light to both gods and men.

What kind of religion did the Greeks have? Now religion may be explained in many different ways, and there have been many different religions in the world, but there has never been a nation that has had no religion. From the earliest times men have realized that there were things in the world that {45}they could not understand, and these mysteries showed them that there must be some Being greater than man who had himself been created; and it is by what is called religion that men have sought to come into relationship with this Being greater than themselves.

The Egyptians in their religious beliefs had been very much occupied with the idea of the life after death, but at first the Greeks thought of this very little. They believed that proper burial was necessary for the future happiness of the soul, and want of this was looked upon as a very serious disaster, but beyond the insisting on due and fitting burial ceremonies their thoughts were not much occupied with the future. The reason of this was probably because the Greeks found this life so delightful. They were filled with the joy of being alive and were keenly interested in everything concerning life; they felt at home in the world. The gods in whom the Greeks believed were not supposed to have created the world, but they were themselves part of it, and every phase of this life that was so full of interest and adventure was represented by the personality of a god. First, it was the outside life, nature with all its mysteries, and then all the outward activities of man. Later, men found other things difficult to explain, the passions within them, love and hatred, gentleness and anger, and gradually they gave personalities to all these emotions and thought of each as inspired by a god. These gods were thought of as very near to man; men and women in the Heroic Age had claimed descent from them, and they were supposed to come {46}down to earth and to hold frequent converse with man. The Greeks trusted their gods and looked to them for protection and assistance in all their affairs, but these gods were too human and not holy enough to be a real inspiration or to influence very much the conduct of those who believed in them.

The chief gods dwelt on Mount Olympus in Thessaly and were called the Olympians; others had dwellings on the earth, in the water, or in the underworld. Heaven, the water and the underworld were each under the particular sovereignty of a great overlord amongst the gods.

Three brethren are we [said Poseidon], Zeus and myself and Hades is the third, the ruler of the folk in the underworld. And in three lots are all things divided, and each drew a domain of his own, and to me fell the hoary sea, to be my habitation for ever, when we shook the lots; and Hades drew the murky darkness, and Zeus the wide heaven, in clear air and clouds, but the earth and high Olympus are common to all.[1]

Zeus was the greatest of the gods. He was the Father of gods and men, the lord of the lightning and of the storm-cloud, whose joy was in the thunder. But he was also the lord of counsel and ruler of heaven and earth, and he was in particular the protector of all who were in any kind of need or distress, and he was the guardian of the home. The court of every house had an altar to Zeus, the Protector of the Hearth. A great statue of Zeus stood in the temple at Olympia. It was the work of Pheidias {47}and was considered one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world.[2] This statue was destroyed more than a thousand years ago by an earthquake, but a visitor to Olympia in ancient times tells us how perfectly it expressed the character of the god:

His power and kingship are displayed by the strength and majesty of the whole image, his fatherly care for men by the mildness and lovingkindness in the face; the solemn austerity of the work marks the god of the city and the law—he seems like to one giving and bestowing blessings.[3]

Hera was the wife of Zeus. She was “golden-throned Hera, an immortal queen, the bride of loud-thundering Zeus, the lady renowned, whom all the Blessed throughout high Olympus honour and revere no less than Zeus whose delight is the thunder.”[4]

Poseidon went to Olympus when he was summoned by Zeus, but he was the God of the Sea, and he preferred its depths as his home. His symbol was the trident, and he was often represented as driving over the waves in a chariot drawn by foaming white horses. All sailors looked to him for protection and they sang to him: “Hail, Prince, thou Girdler of the Earth, thou dark-haired God, and with kindly heart, O blessed one, do thou befriend the mariners.”[5]

Athena, the grey-eyed Goddess, was the Guardian of Athens, and she stood to all the Greeks, but especially to the Athenians, as the symbol of three {48}things: she was the Warrior Goddess, “the saviour of cities who with Ares takes keep of the works of war, and of falling cities and the battle din.”[6] She it was who led their armies out to war and brought them home victorious. She was Athena Polias, the Guardian of the city and the home, to whom was committed the planting and care of the olive trees and who had taught women the art of weaving and given them wisdom in all fair handiwork; she was the wise goddess, rich in counsel, who inspired the Athenians with good statesmanship and showed them how to rule well and justly; and she was Athena Parthenos, the Queen whose victories were won, and who was the symbol of all that was true and beautiful and good.

Apollo, the Far Darter, the Lord of the silver bow, was the god who inspired all poetry and music. He went about playing upon his lyre, clad in divine garments; and at his touch the lyre gave forth sweet, music. To him

everywhere have fallen all the ranges of song, both on the mainland and among the isles: to him all the cliffs are dear, and the steep mountain crests and rivers running onward to the salt sea, and beaches sloping to the foam, and havens of the deep.

When Apollo the Far Darter “fares through the hall of Zeus, the Gods tremble, yea, rise up all from their thrones as he draws near with his shining bended bow.”[7] Apollo was also worshipped as Phoebus the {49}Sun, the God of Light, and like the sun, he was supposed to purify and illumine all things.

Following Apollo as their lord were the Muses, nine daughters of Zeus, who dwelt on Mount Parnassus. We are told that their hearts were set on song and that their souls knew no sorrow. It was the Muses and Apollo who gave to man the gift of song, and he whom they loved was held to be blessed. “It is from the Muses and far-darting Apollo that minstrels and harpers are upon the earth. Fortunate is he whomsoever the Muses love, and sweet flows his voice from his lips.”[8] The Muse who inspired man with the imagination to understand history aright was called Clio.

The huntress Artemis, the sister of Apollo, was goddess of the moon as her brother was god of the sun. She loved life in the open air and roamed over the hills and in the valleys, through the forests and by the streams. She was the

Goddess of the loud chase, a maiden revered, the slayer of stags, the archer, very sister of Apollo of the golden blade. She through the shadowy hills and the windy headlands rejoicing in the chase draws her golden bow, sending forth shafts of sorrow. Then tremble the crests of the lofty mountains, and terribly the dark woodland rings with din of beasts, and the earth shudders, and the teeming sea.[9]

Hermes is best known to us as the messenger of the gods. When he started out to do their bidding,

{50}beneath his feet he bound on his fair sandals, golden, divine, that bare him over the waters of the sea and over the boundless land with the breathings of the wind. And he took up his wand, wherewith he entranceth the eyes of such men as he will, while others again he awaketh out of sleep.[10]

Hermes was the protector of travellers, and he was the god who took special delight in the life of the market place. But there was another side to his character, he was skilful in all matters of cunning and trickery, and legend delighted in telling of his exploits. He began early. “Born in the dawn,” we are told, “by midday well he harped and in the evening stole the cattle of Apollo the Far Darter.”[11]

Hephaestus was the God of Fire, the divine metal-worker. He was said to have first discovered the art of working iron, brass, silver and gold and all other metals that require forging by fire. His workshop was on Mount Olympus and here he used to do all kinds of work for the gods. Perhaps his most famous piece was the divine armour and above all the shield he made for Achilles. Some great quarrel in which he was concerned arose in Olympus, and Zeus, in rage, threw him out of heaven. All day he fell until, as the sun was setting, he dropped upon the isle of Lemnos.

Athena and Hephaestus were always regarded as benefactors to mankind, for they taught man many useful arts.

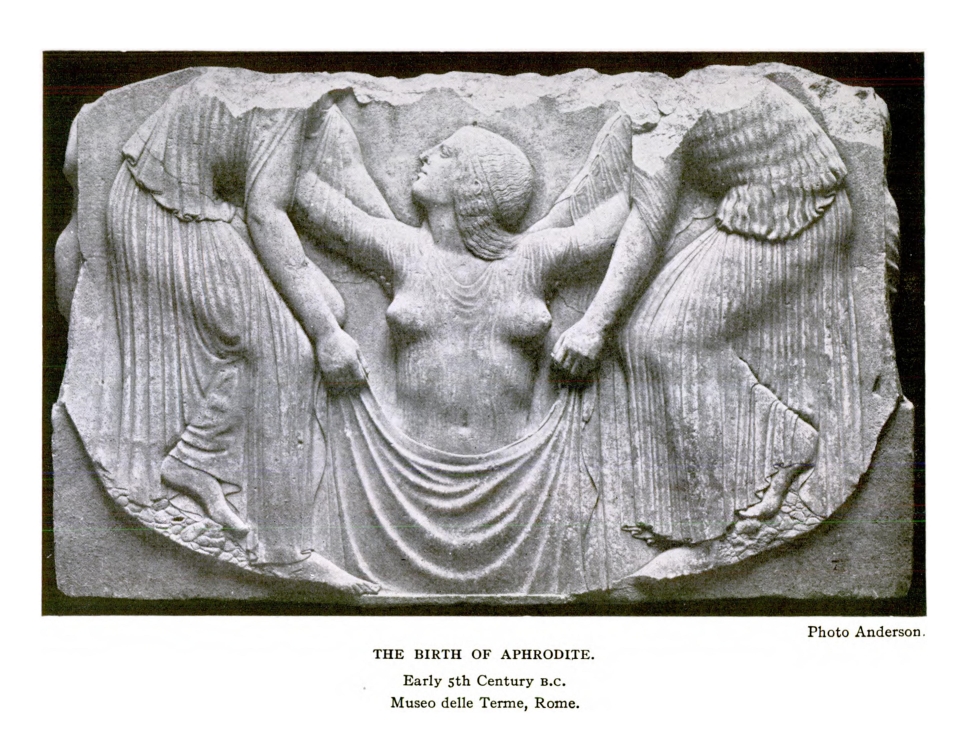

THE BIRTH OF APHRODITE.

Early 5th Century B.C.

Museo delle Terme, Rome.

Sing, Muse, of Hephaestus renowned in craft, who with grey-eyed Athena taught goodly works to men on earth, even to men who before were wont to dwell in mountain caves like beasts; but now, being instructed in craft by the renowned craftsman Hephaestus, lightly the whole year through they dwell, happily in their own homes.[12]

Hestia, the Goddess of the Hearth, played an important part in the life of the Greeks. Her altar stood in every house and in every public building, and no act of any importance was ever performed, until an offering of wine had been poured on her altar.

Laughter-loving, golden Aphrodite was the Goddess of Love and Beauty. She rose from the sea born in the soft white foam. “She gives sweet gifts to mortals and ever on her lovely face is a winsome smile.”[13]

To the ancient Greeks the woods and streams, the hills and rocky crags of their beautiful land were dwelt in by gods and nymphs and spirits of the wild. Chief of such spirits was Pan,

the goat-footed, the two-horned, the lover of the din of the revel, who haunts the wooded dells with dancing nymphs that tread the crests of the steep cliffs, calling upon Pan. Lord is he of every snowy crest and mountain peak and rocky path. Hither and thither he goes, through the thick copses, sometimes being drawn to the still waters, and sometimes faring through the lofty crags {52}he climbs the highest peaks whence the flocks are seen below; ever he ranges over the high white hills and at evening returns piping from the chase breathing sweet strains on the reeds.[14]

These were the chief gods in whom the Greeks believed. How did they worship them? The centre of their worship was the altar, but the altars were not in the temples, but outside. They were also found in houses and in the chief public buildings of the city. The temple was looked upon as the home of the god, and the temple enclosure was a very sacred place. A man accused of a crime could flee there and take refuge, and once within the temple, he was safe. It was looked upon as a very dreadful thing to remove him by force, for it was believed that to do so would bring down the wrath of the god upon those who had violated the right of sanctuary.

In the houses the altars were those sacred to Hestia, to Apollo and to Zeus. The altar of Hestia stood in the chief room of the house, a libation was poured out to her before meals, and special sacrifices were offered on special occasions; always before setting out on a journey and on the return from it, and at the time of a birth or of a death in the house. The altar of Apollo stood just outside the door. Special prayers and sacrifices were offered at this altar in times of trouble, but Apollo was not forgotten in the time of joy: those who had travelled far from home stopped to worship on their return; when good news came to the house sweet-smelling {53}herbs were burnt on his altar, and a bride took sacred fire from it to offer to Apollo in her new home.

The Greeks had no stated day every week sacred to the gods, but during the year different days were looked upon as belonging specially to particular gods. Some of these days were greater than others and were honoured by public holidays. Others caused no interruption in the every-day life.

Priests were attached to the temples, but sacrifices on the altars in the city or in the home were presented by the king or chief magistrate and by the head of the household. The Greeks did not kneel when they prayed, but stood with bared heads. Their prayers were chiefly for help in their undertakings. They prayed before everything they did: before athletic contests, before performances in the theatre, before the opening of the assembly. The sailor prayed before setting out to sea, the farmer before he ploughed and the whole nation before going forth to war. Pericles, the great Athenian statesman, never spoke in public without a prayer that he might “utter no unfitting word.”

As time went on, the gods of Olympus seemed less near to mortal men, and they gradually became less personalities than symbols of virtues, and as such they influenced the conduct of men more than they had done before. Athena, for example, became for all Greeks the symbol of self-control, of steadfast courage and of dignified restraint; Apollo of purity; and Zeus of wise counsels and righteous judgments.

A particular form of worship specially practised by the Athenians was that known as the Sacred {54}Mysteries, which were celebrated every autumn and lasted nine days. This worship centred round Demeter and was celebrated in her temple at Eleusis near Athens. Demeter was the Corn-Goddess and it was the story of her daughter Persephone who was carried off by Hades, lord of the realm of the dead, that was commemorated in the Sacred Mysteries.

Her daughter was playing and gathering flowers, roses and crocuses and fair violets in the soft meadow, and lilies and hyacinths, and the narcissus. Wondrously bloomed the flower, a marvel for all to see, whether deathless gods or deathly men. From its root grew forth a hundred blossoms, and with its fragrant odour the wide heaven above and the whole earth laughed, and the salt wave of the sea. Then the maiden marvelled and stretched forth both her hands to seize the fair plaything, but the wide earth gaped, and up rushed the Prince, the host of many guests, the son of Cronos, with his immortal horses. Against her will he seized her and drove her off weeping and right sore against her will, in his golden chariot, but she cried aloud, calling on the highest of gods and the best … and the mountain peaks and the depths of the sea rang to her immortal voice.[15]

Demeter heard the cry, but could not save her daughter, and she went up and down the world seeking her. She reached Attica and was kindly treated, though the people did not at first know she was a goddess. When she had revealed herself to them, she commanded them to build her a temple {55}at Eleusis. But still her daughter did not return to her, and the gods of Olympus took no heed of her lamenting. Then she put forth her power as Goddess of the Corn, and she caused it to stop growing over all the earth. A fearful famine followed, and Zeus tried to persuade her to relent. But she declared that “she would no more forever enter on fragrant Olympus, and no more allow the earth to bear her fruit until her eyes should behold her fair-faced daughter.”[16]

At last Zeus consented to interfere and sent Hermes to bring Persephone back to the earth. When Persephone saw the messenger, “joyously and swiftly she arose and she climbed up into the golden chariot and drove forth from the halls; nor sea, nor rivers, nor grassy glades, nor cliffs could stay the rush of the deathless horses,”[17] until they reached the temple where dwelt Demeter, who when she beheld them rushed forth to greet her daughter. But before leaving Hades, the God had given Persephone a sweet pomegranate seed to eat, a charm to prevent her wishing to dwell forever with Demeter, and it was then arranged that Persephone should dwell with Hades, the lord of the realm of the dead, for one-third of the year, and for the other two-thirds with her mother and the gods of Olympus.

This was the story round which centred the worship of the Sacred Mysteries at Eleusis. There came a time when the worship of the gods of Olympus did not satisfy the longings of the Greeks for some assurance that the soul was immortal and that there {56}was a life after the death of the body. Demeter grew to be a symbol to the Greeks of the power of the gods to heal and save and to grant immortality. Her story became an allegory of the disappearance of the corn and fruit and flowers in the winter and of their return in the spring, bringing with them gifts to men of hope and life. At the festival of Eleusis, a kind of mystery play on the whole legend was acted. All those who attended the festival were required to prepare for it by a certain ritual of fasting and sacrifice, and it was believed that in the life after death all would be well with those who had taken part in the festival with pure hearts and pure hands.

The greatest religious influence in Greece was probably that of the Oracle. This was the belief that at certain shrines specially sacred to certain gods, the worshipper could receive answers to questions put to the god. In very early times signs seen in the world of nature were held to have special meanings: the rustling of leaves in the oak-tree, the flight of birds, thunder and lightning, eclipses of both the sun and moon or earthquakes. It is easy to understand how this belief arose. A man, perplexed and troubled by some important decision he had to make, would leave the city with its bustle and noise, and go out into the country where he could think out his difficulty alone and undisturbed. Perhaps he would sit under a tree, and as he sat and thought, the rustling of the leaves in the breeze would soothe his troubled mind and slowly his duty would become clear to him, and it would seem to {57}him that his questions were answered. Looking up to the sky he would give thanks to Zeus for thus inspiring him with understanding. On his return home he would speak of how he had heard the voice of Zeus speaking to him in the rustling of the leaves, and so the place would gradually become associated with Zeus, and others would go there and seek answers to their difficulties, hoping to meet with the same experience, until at last the spot would become sacred and a shrine would be built there, and it would at length become known from far and near as an Oracle. Plato said of these beginnings of the oracles that “for the men of that time, since they were not so wise as ye are nowadays, it was enough in their simplicity to listen to oak or rock, if only these told them true.” Other places would in the same way become associated with other gods, until seeking answers at Oracles became a well-established custom in Greece.

The great oracles of Zeus were at Olympia, where the answers were given from signs observed in the sacrifices offered, and at Dodona, where they were given from the sound of the rustling of the leaves in the sacred oak-tree. But the greatest oracle in all Greece was that of Apollo at Delphi. It was at Delphi that Apollo had fought with and slain the Python, and it was thought that he specially delighted to dwell there, and had himself chosen it as the place where he would make known his will.

Here methinketh to stablish a right fair temple, to be a place of oracle to men, both they that dwell in rich {58}Peloponnesus and they of the mainland and sea-girt isles, seeking here the word of wisdom; to them all shall I speak the decree unerring, rendering oracles within my wealthy shrine.[18]

Delphi had been sacred to Apollo ever since these legendary days, and a great shrine and temple was built there in his honour.

When a Greek came to consult Apollo, he had first to offer certain sacrifices, and he always brought with him the richest gifts he could afford which were placed in the treasury of the god. Then he entered the temple and placed his request in the hands of a priest, who took it into the innermost sanctuary and gave it to the prophetess, whose duty it was to present the petition to the god himself and receive the answer. In ancient times it was believed that a mysterious vapour arose in this sanctuary through a cleft in the rocky floor, and that this vapour, enveloping the prophetess, filled her with a kind of frenzy in the midst of which she uttered the words of the answer given her by Apollo. This answer was written down by the priests and often turned into verse by them and then taken out to the enquirer. Sometimes these answers were quite plain and straightforward, such as the one which has remained true through all the ages. It was the oracle from Apollo at Delphi which said of the poet Homer: “He shall be deathless and ageless for aye.” But sometimes the answers were like a riddle that required much thinking over to understand, and {59}sometimes they were so worded that they might mean either of two things, each the opposite of the other! The oracle at Delphi was frequently consulted by the Greeks at great crises of their history, and it had great influence. It was the priests who in writing down the answer really determined its nature. They were men who were in constant touch with distant places, they had had much experience with human nature, and they were well fitted to give guidance and advice in all kinds of difficult matters. The oracle at Delphi was thus a power in the worldly affairs of the Greeks, but it was more than that, it was also a source of moral inspiration. It encouraged all manner of civilization and the virtues of gentleness and self-control, it marked the great reformers with its approval, it upheld the sanctity of oaths, it encouraged respect and reverence for women. On one of the temples were inscribed the sayings “Know thyself” and “Nothing in excess.” It was said that these had been placed there by the ancient sages, and in later times they became famous as maxims in the teaching of the great philosophers.

The oracle was not always right in its interpretations; it sometimes failed in seizing the highest opportunities that lay before it, but as Greek history unfolds itself before us, we can see a gradual raising of moral standards, which was due in great measure to the influence of the oracle of Apollo at Delphi.

[1] Iliad, XV.

[2] See p. 64.

[3] Dion Chrysostom.

[4] Homeric Hymn to Hera.

[5] Homeric Hymn to Poseidon.

[6] Homeric Hymn to Athena.

[7] Homeric Hymn to Apollo.

[8] Homeric Hymn to Apollo.

[9] Homeric Hymn to Artemis,

[10] Odyssey, V.

[11] Homeric Hymn to Hermes.

[12] Homeric Hymn to Hephaestus.

[13] Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite.

[14] Homeric Hymn to Pan.

[15] Homeric Hymn to Demeter.

[16] Homeric Hymn to Demeter.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Homeric Hymn to Apollo.