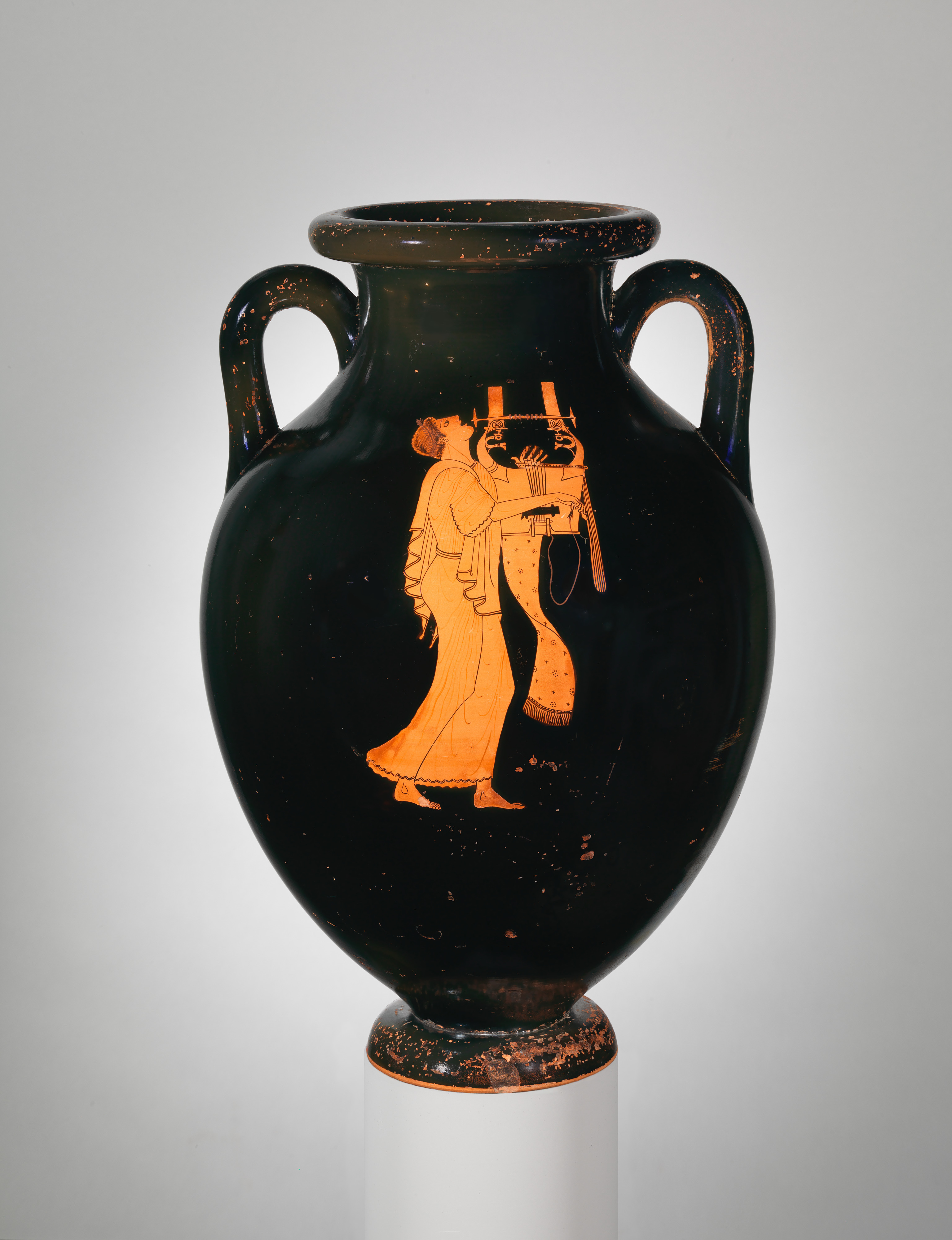

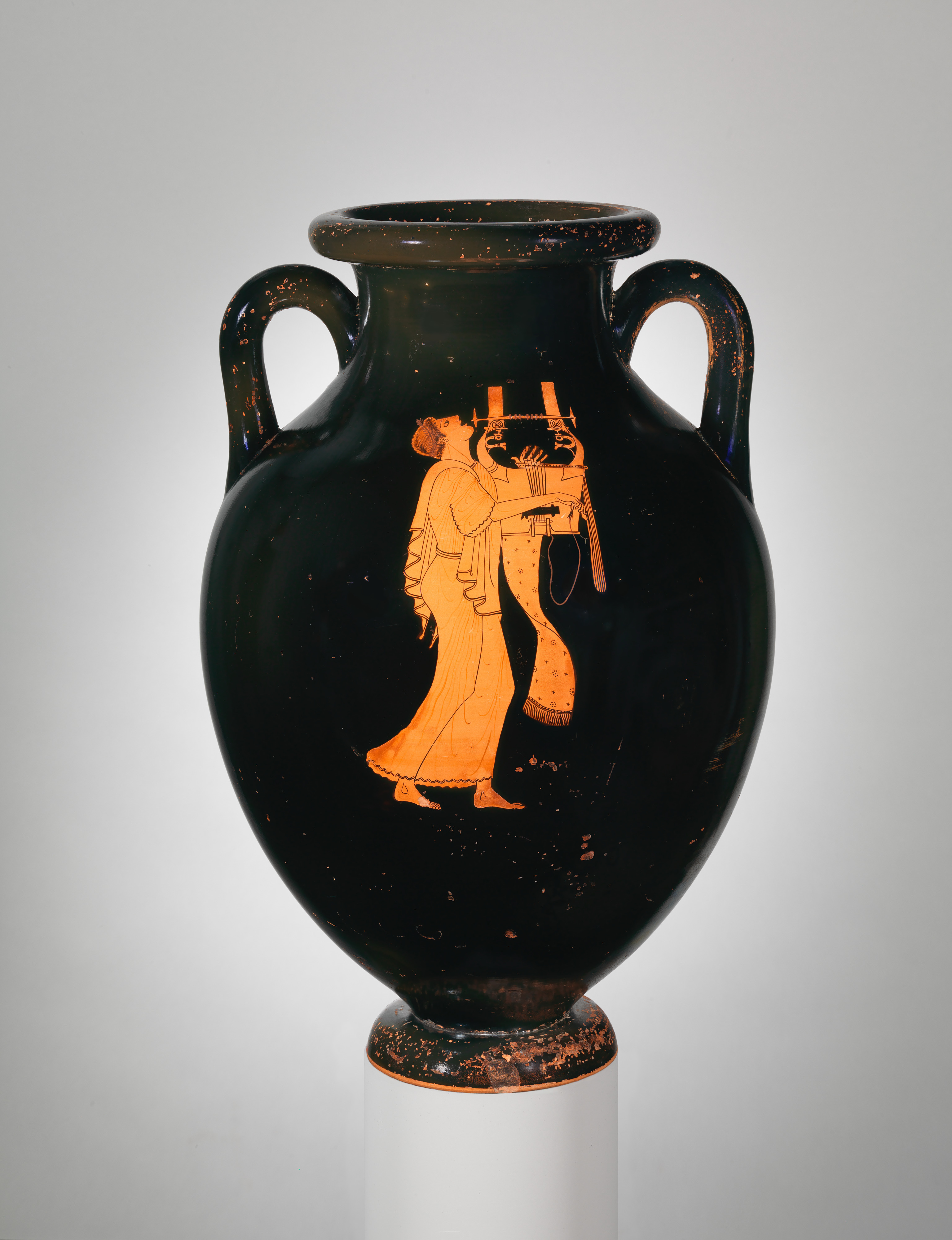

Terracotta amphora (jar)

ca. 490 B.C.

Attributed to the Berlin Painter

“This work is a masterpiece of Greek vase-painting because it brings together many features of Athenian culture in an artistic expression of the highest quality. The shape itself is central to the effect. Through the symmetry, scale, and luminously glossy glaze on the obverse, it offers a carefully composed three-dimensional surface that endows the subject with volume. The identity of the singer is given by his instrument, the kithara, which was a type of lyre used in public performances, including recitations of epic poetry.

“The figure on the reverse is identified by his garb and wand. While the situation is probably a competition, the subject is the music itself. It transports the performer, determines his pose, and causes the cloth below the instrument to sway gently.” The Met

Terracotta pyxis (box)

ca. 465–460 B.C.

Attributed to the Penthesilea Painter

“During the middle of the fifth century B.C., the white-ground technique was commonly used for lekythoi, oil flasks placed on graves, and for fine vases of other shapes. As classical painters sought to achieve ever more complex effects with the limited possibilities of red-figure, the white background gave new prominence to the glaze lines and polychromy. The decoration of this pyxis reflects the delight with which an accomplished artist like the Penthesilea Painter depicted a traditional subject.” The Met

Bronze Mirror with a Support in the form of a draped Woman –

“The ancient Greeks used mirrors that were held in the hand or stood independently. This free-standing example of a well established type consists of a ibase, a supporting figure, and the mirror disk embellished with additional figures around its periphery. The woman, who is probably mortal, wears a woolen garment, a peplos.

“Above her fly two personifications of love, erotes; originally hounds and hares would have coursed around the disk and a sphinx or sren would have perched on top. The variety of component parts are integrated into a whole that is both balanced and dynamic.” The Met

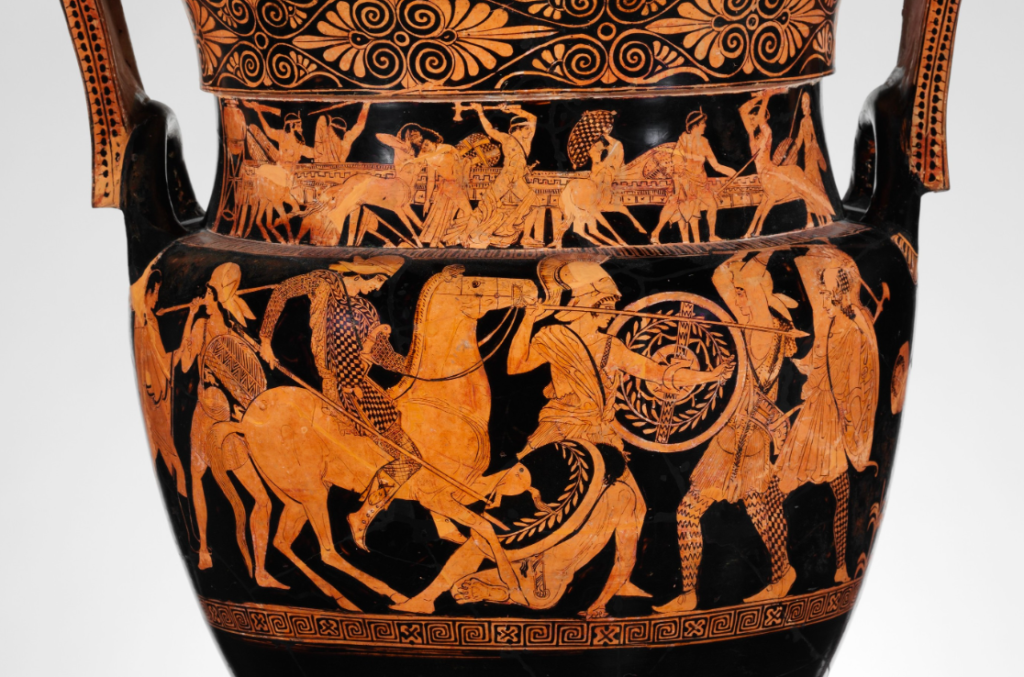

Terracotta volute-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water) ca. 450 B.C. Attributed to the Painter of the Woolly Satyrs

“On the neck, obverse, battle of centaurs and Lapiths; reverse, youths and women

Around the body, Amazonomachy (battle between Greeks and Amazons)

“The ancient Greeks almost never depicted contemporary or historical events in art. Thus, while literary works of the fifth century B.C. make clear that the Greeks understood the magnitude of their victory in the Persian Wars, there was no concern among artists to illustrate major events or personalities.

“Instead, their preference was for grand mythological battles between Greeks and eastern adversaries, notably Amazons. On the neck, obverse, battle of centaurs and Lapiths; reverse, youths and women

Around the body, Amazonomachy (battle between Greeks and Amazons)

The ancient Greeks almost never depicted contemporary or historical events in art. Thus, while literary works of the fifth century B.C. make clear that the Greeks understood the magnitude of their victory in the Persian Wars, there was no concern among artists to illustrate major events or personalities. Instead, their preference was for grand mythological battles between Greeks and eastern adversaries, notably Amazons. The Amazons were a mythical race of warrior women whose homeland lay far to the east and north. The most celebrated Amazonomachies in Athens during the first half of the fifth century were large-scale wall paintings that decorated the Theseion and the Stoa Poikile (the Painted Portico). Their influence was considerable and underlies the representation here and on the adjacent krater, 06.286.86. The most celebrated Amazonomachies in Athens during the first half of the fifth century were large-scale wall paintings that decorated the Theseion and the Stoa Poikile (the Painted Portico). Their influence was considerable and underlies the representation here and on the adjacent krater, 06.286.86.

Marble grave stele of a little girl ca

“The gentle gravity of this child is beautifully expressed through her sweet farewell to her pet doves. Her peplos is unbelted and falls open at the side, while the folds of drapery clearly reveal her stance. Many of the most skillful stone carvers came from the Cycladic Islands, where marble was plentiful. The sculptor of this stele could have been among the artists who congregated in Athens during the third quarter of the fifth century B.C. to decorate the Parthenon.” The Met

“The middle of the fifth century B.C. is often referred to as the Golden Age of Greece, particularly of Athens. Significant achievements were made in Attic vase painting. Most notably, the red-figure technique superseded the black-figure technique, and with that, great strides were made in portraying the human body, clothed or naked, at rest or in motion. The work of vase painters, such as Douris, Makron, Kleophrades, and the Berlin Painter (56.171.38), exhibit exquisitely rendered details.

“Although the high point of Classical expression was short-lived, it is important to note that it was forged during the Persian Wars (490–479 B.C.) and continued after the Peloponnesian War (431–404 B.C.) between Athens and a league of allied city-states led by Sparta. The conflict continued intermittently for nearly thirty years. Athens suffered irreparable damage during the war and a devastating plague that lasted over four years. Although the city lost its primacy, its artistic importance continued unabated during the fourth century B.C. The elegant, calligraphic style of late fifth-century sculpture (35.11.3) was followed by a sober grandeur in both freestanding statues (06.311) and many grave monuments (11.100.2).

“One of the far-reaching innovations in sculpture at this time, and one of the most celebrated statues of antiquity, was the nude Aphrodite of Knidos, by the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles. Praxiteles’ creation broke one of the most tenacious conventions in Greek art in which the female figure had previously been shown draped. Its slender proportions and distinctive contrapposto stance became hallmarks of fourth-century B.C. Greek sculpture. In architecture, the Corinthian—characterized by ornate, vegetal column capitals—first came into vogue. And for the first time, artistic schools were established as institutions of learning. Among the most famous was the school at Sikyon in the Peloponnesos, which emphasized a cumulative knowledge of art, the foundation of art history. Greek artists also traveled more extensively than in previous centuries. The sculptor Skopas of Paros traveled throughout the eastern Mediterranean for his commissions, among them the Mausoleum at Halicarnassos, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

While Athens began to decline during the fourth century B.C., the influence of Greek cities in southern Italy and Sicily spread to indigenous cultures that readily adopted Greek styles and employed Greek artists. Depictions of Athenian drama, which flourished in the fifth century with the work of Aeschylus, Sophokles, and Euripides, was an especially popular subject for locally produced pottery (24.97.104).

During the mid-fourth century B.C., Macedonia (in northern Greece) became a formidable power under Philip II (r. 360/359–336 B.C.), and the Macedonian royal court became the leading center of Greek culture. Philip’s military and political achievements ably served the conquests of his son, Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 B.C.). Within eleven years, Alexander subdued the Persian empire of western Asia and Egypt, continuing into Central Asia as far as the Indus River Valley. During his reign, Alexander cultivated the arts as no patron had done before him. Among his retinue of artists was the court sculptor Lysippos, arguably one of the most important artists of the fourth century B.C. His works, most notably his portraits of Alexander (and the work they influenced), inaugurated many features of Hellenistic sculpture, such as the heroic ruler portrait (52.127.4). When Alexander died in 323 B.C., his successors, many of whom adopted this portrait type, divided up the vast empire into smaller kingdoms that transformed the political and cultural world during the Hellenistic period (ca. 323–31 B.C.).”

Hemingway, Colette, and Seán Hemingway. “The Art of Classical Greece (ca. 480–323 B.C.).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tacg/hd_tacg.htm (January 2008)