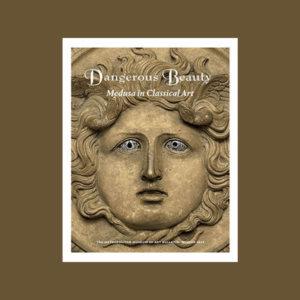

“Dangerous Beauty: Medusa in Classical Art : The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2018/dangerous-beauty. Accessed 6 Sept. 2022.

“The exhibition publication explores the ways in which Medusa and other hybrid creatures were depicted from antiquity to the present day.” The Met

“Beginning in the fifth century b.c., the Gorgon Medusa—a legendary monster whose gaze could turn beholders to stone—underwent a visual transformation from grotesque to beautiful, becoming in the process increasingly anthropomorphic and feminine. A similar shift in the representations of other mythical female half-human beings (or hybrids), such as sphinxes, sirens, and the sea monster Scylla, took place at the same time.1 The iconographic makeover of these inherently terrifying figures—symbols of death and the Underworld believed to have

apotropaic (protective) powers—was a result of the idealizing humanism of Greek art of the Classical period (480–323 b.c.). Hybrids continued to evolve in form and meaning after the Classical period, however, and many still resonate in modern culture and the artistic imagination.2

Monsters and the Genealogy of Terror

“Throughout human history, monsters have emerged as figments of the imagination in various cultures.3 These fearsome supernatural beings, often hybrid in form, share many characteristics: they are usually gigantic, malevolent, and violent, and frequently reptilian, ugly, or bizarre-looking. They idealizing humanism of Greek

art of the Classical period (480–323 b.c.).

“A metaphor for nature’s threatening forces, they can also symbolize innate human fears and anxieties, sexual aggression, and guilt. Often described as monsters or demons, a wide repertoire of theriomorphic creatures— combining animal parts with human features and

fantastical appendages—was introduced to the Greek world from the Near East and Egypt

during the late eighth and seventh centuries b.c. Imbued with protective powers, these figures

functioned as apotropaia, or talismans that turn away evil, and as such were frequently employed on sepulchral monuments, sacred architecture, military equipment, drinking vessels, and the luxury arts.

“The majority of Greek hybrid beings were imagined as female, blending the human female

form with elements from animals such as snakes, birds, lions, dogs, and fish. Most were also related by parentage or common ancestry and symbolized a primordial, grisly vision of the terror of the sea. Phorkys and Keto, sea deities and children of the god Pontos (Ocean), bore the three Gorgons; the three Graiai (old women from birth who shared one eye and one tooth among themselves); the sirens;4 and the dreadful Echidna, halfwoman and half-snake, who in turn mothered Scylla, the Harpies, and Hydra.

“Reshuffling what was familiar, hybrids represented all that was alien, the “Other.” Morphological oddities such as hybrids were considered anomalies in ancient Greece and, thus, of a [pg. 5]destructive nature. At the same time, in a society centered on the male citizen, the feminization of monsters served to demonize women. Wronged by men and overcome with rage and desperation, heroines of ancient Greek drama such as Clytemnestra and Medea commit monstrous acts and were judged deviant females who threatened cultured society. For this reason tragedians often compared them to Medusa and other female monsters and beasts.

“Beginning in the fifth century b.c., as the grotesque monsters of the Archaic period were

rethought, rationalized, and humanized, their animalistic features were progressively softened, and female hybrids became more beautiful in appearance, or, in the words of classicist Susan Woodford, “aesthetically improved to suit the sensibilities of the classical period,” when ugliness was largely avoided.5

“In ancient Greece, the concept of beauty, whether of animate beings or inanimate objects, was understood as harmony and proportion among constituent parts. A beautiful form delighted the senses.6 Physical beauty was always connected with goodness of character—the Greek ideal of kalokagathia—and since it was thought that character was reflected in one’s physiognomy, physical ugliness connoted moral ugliness.

“In his Poetics, Aristotle argued that it is possible to make beautiful imitations of ugly things.

It is precisely the power of art to portray ugly and horrible creatures in a beautiful way that renders their ugliness acceptable, even pleasurable.7

“This connection of beauty with horror, embodied above all in the figure of Medusa, outlived antiquity and continued to fascinate and inspire artists for centuries.8

“Medusa, in effect, became the archetypal femme fatale: a conflation of femininity, erotic desire, violence, and death. Beauty, like monstrosity, enthralls, and female beauty in particular was perceived—and, to a certain extent, is still perceived—to be both enchanting and dangerous, or even fatal. In this sense, even Helen of Troy, considered the personification of ideal beauty, was deemed responsible, albeit inadvertently, for the Trojan War and the

ultimate destruction of Troy

“Perseus and the Gorgon Medusa

“The three Gorgons—Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa—were terrible monsters who lived in the

Western Ocean, conceived as the frontier of the inhabited world (Hesiod, Theogony 274–75). The Gorgons had large heads covered in dragon scales, boar’s tusks, brazen hands, and golden wings. Whoever looked at their hideous faces turned instantly to stone. Of the three sisters, only Medusa was mortal. She is the most famous Gorgon because of her role in the legend of the hero Perseus, who is the great-grandfather of Herakles, the quintessential monster-slayer of Greek mythology.

“The most extensive narrative of the Perseus Medusa encounter is preserved in the Bibliotheke (Library 2.4.1–4) of pseudo-Apollodorus, a first- or second-century a.d. compiler whose account relied on at least one fifth-century b.c. source, the Athenian mythographer Pherekydes.

“According to this version, Akrisios, the king of Argos, received an oracle that his grandson by his daughter Danaë would kill him. To avoid this fate, he imprisoned Danaë in an underground bronze chamber, where she could not be approached by suitors. Zeus, however, fell in love with her and seduced her after penetrating the chamber as a stream of gold. As a result of this union, Danaë bore Zeus’s son Perseus. Upon learning this, Akrisios shut both mother and child in a wooden chest and cast it into the sea. The chest floated to the island of Seriphos, where Danaë and Perseus were rescued and looked after by a fisherman named Diktys. In time, the island’s tyrannical [pg. 6] king, Polydektes—Diktys’s brother—wanted Danaë for his wife, but Perseus opposed the match. On the pretext of gathering contributions toward a wedding gift for the Peloponnesian princess Hippodameia, Polydektes asked the island’s noblemen to furnish horses but accepted instead the young hero’s boastful offer to bring him a

Gorgon’s head.

“With the help of Hermes, Athena, and the nymphs, Perseus equipped himself with an adamantine sickle (harpe); winged sandals; the cap of Hades (kunee), which rendered him invisible; and the kibisis, a pouch in which to put the Gorgon’s head. After receiving instructions on how to find and kill Medusa, Perseus flew to the Ocean and found the Gorgons asleep. Averting his eyes to avoid their petrifying gaze, Perseus used a bronze shield as a mirror and, with Athena’s guidance, cut off Medusa’s head and escaped the pursuit of her two sisters.

“On his journey back to Seriphos, he rescued the Ethiopian princess Andromeda, whom he

found chained to a rock as sacrifice to a sea monster, and married her. Upon his return to the

island he brought Medusa’s head to the palace, using it to turn king Polydektes and his entourage to stone, thereby saving his mother from the unwanted marriage. He then appointed Diktys king of Seriphos and gave Athena the Gorgon’s head, which she put on her shield. In the end, the oracle was fulfilled when Perseus inadvertently killed his grandfather Akrisios with a misthrown discus during funeral games in Larissa.

“The Perseus story is a classic folktale hero’s quest, in which a malevolent king sends a hero—

typically someone of noble or, usually, semidivine descent and malign destiny—on a suicide

mission that involves slaying a monster or bringing back some distant magical object. He accomplishes this task with the help of the gods, overcoming obstacles along the way and, quite

often, winning the maiden upon his return, whereupon, as one scholar put it, “the nasty king

dies messily.”9 The essential plot—a young, brave, and handsome hero sets off to slay a hideous and wicked monster—is familiar to us from countless reiterations and adaptations in literature, comicbooks, and blockbuster movies.

The Beautiful Medusa

“In the Roman poet Ovid’s retelling of the Medusa myth from the early first century a.d. (Metamorphoses 4.778–803), Perseus himself narrates his encounter with the Gorgon during the celebration of his wedding to Andromeda at the court of the Ethiopian king Cepheus. The hero describes the nightmarish landscape he encountered on the way: “On all sides through the fields and along the ways he saw the forms of men and beasts changed into stone by one look at Medusa’s face. But he himself had looked upon the image of that dread face reflected from the bright bronze shield his left hand bore; and while deep sleep held fast both the snakes and her who wore them, he smote her head clean from her neck, and from

the blood of his mother swift-winged Pegasus and his brother sprang.”10 The visage of Medusa

reflected on a polished bronze shield can be seen on a late Classical South Italian krater (fig. 1).

“When asked why Medusa alone of the Gorgons had snakes entwined in her hair, Perseus explains that she was the most beautiful of the three sisters, endowed with hair that was widely admired. After Neptune (Poseidon) raped her inside the temple of Minerva (Athena), the goddess changed Medusa’s hair into foul snakes as punishment.

Henceforth, Minerva wore the snaky head on her breast to frighten her enemies, as pictured on a red-figure lekythos (fig. 2).

Terracotta lekythos (oil flask)

ca. 480 B.C.

Attributed to the Tithonos Painter

Athena holding spear and helmet

“Athena, the warlike protector of Athens, appears alert but serene on this vase. Dressed in a full, richly decorated peplos with a diadem in her hair, she holds her helmet in one hand and her spear, pointed downward, in the other. Her aegis, the protective goatskin ringed with snakes’ heads, acts as armor.” The Met

“Although in Ovid’s version Medusa is the victim rather than the perpetrator, her violation is portrayed as a desecration of sacred space that brings down the virgin goddess’s wrath upon her.

“This transition from the tale of a hero combating a monster to the sad story of a beautiful

maiden transformed into a monster affected artistic representations of the myth. The striking contrast between the monstrous Archaic Gorgons and the beautiful Hellenistic and Roman Medusae was recognized in the late nineteenth century by noted archaeologist Adolf Furtwängler, who devised an evolutionary model of Medusa based on three types: the Archaic, the Middle (representing the intermediate stage in the fifth century b.c., when grotesque elements were still present in artistic depictions), and the Beautiful.11

Despite challenges by recent scholars, his typology remains broadly applicable.12

In Archaic Greek art, the Gorgon Medusa is shown both as a full female figure dressed in a

short chiton (fig. 4) and as a severed head or mask, known as the Gorgoneion. In either representation the Gorgon has a porcine face, with fierce, bulging eyes; a large, simian nose; a wide, grinning mouth; and a protruding tongue. On an Archaic stand in The Met collection her bared, serrated teeth are bordered by two pairs of tusks (fig. 3).

Terracotta stand

ca. 570 B.C.

Signed by Ergotimos

Signed by Kleitias

“Ergotimos and Kleitias signed a large volute-krater, now in the Archaeological Museum, Florence, that is a veritable compendium of Greek mythology, particularly relating to Achilles. This stand is the only other preserved work with their signatures. The three Gorgons were so horrible-looking that whoever saw them turned to stone. In Archaic art, the face is a frequent motif, partly because it fits well into a circular format.” The Met

“She also has the stubble of a mustache, a full beard, stylized locks of hair, and pierced ears.

Ranging from the fearsome to the grotesque, the features that make up her hideous countenance are more characteristic of masks than of specific animal representations. The Archaic Gorgon is always full-face, moreover, glaring directly at the viewer. This combination of frontality and monstrosity in a single, immediately recognizable figure is what makes the Greek Gorgon such an original and evocative image of radical difference: of the absolute “Other.”13

“Gorgons were often carved on funerary monuments as apotropaic images intended to protect the grave. Medusa’s association with death is unsurprising, not only because of her petrifying gaze but also considering her own mortality; she embodies the ugly truth that death is an inescapable aspect of life.

“An Attic marble grave stele (fig. 5) represents a Gorgon in pursuit of Perseus after Medusa’s decapitation. Rushing through the air, the Gorgon spreads her wings wide and moves her arms and legs forcefully in a pinwheel motion, an iconographic convention frequently employed in Archaic art to denote speed.

Part of the marble stele (grave marker) of Kalliades

550–525 BC

Greek, Attic

“A fleeing Gorgon decorates this tapering, predella-looking slab, part of the grave stele of Kalliades, as we learn from the inscription carved in three lines from left to right below the Gorgon’s left knee: “Kalliades, son of Thoutimides”.

The Gorgon, dressed in a short chiton, spreads her wings wide and moves her arms and legs forcefully as she rushes through air. Her head and upper torso are rendered frontally, while her lower torso and legs are shown in profile and bent at the knees in the so-called “knie-lauf” schema, an iconographic convention frequently employed in Archaic Art to denote speed. Mythological creatures like gorgons and sphinxes often functioned as apotropaic images that protected the grave.” The Met

Terracotta pelike (jar)

ca. 450–440 B.C.

Attributed to Polygnotos

Obverse, Perseus beheading the sleeping Medusa

“King Polydektes sent Perseus to obtain the head of the Gorgon Medusa, a monstrous, snaky-haired, winged creature with glaring eyes whose gaze turned beholders to stone. Perseus accomplished his mission with the help of Athena, Hermes and the Nymphs, and returned to the island of Seriphos whence he had set out. By the mid-fifth century B.C., the story and the motif of the Gorgon’s head had become popular in Attic art. Perseus looks unwaveringly at his protectress, Athena as he is about to behead the sleeping Medusa. The rendering here is unusual, however, because it is one of the earliest in which Medusa’s face is that of a beautiful young woman. Another important feature here, although not longer readily visible, is that rays surround the hero’s head, indicating special stature or power.

“Compared with the movement and detail on the obverse, the reverse shows a grand and quiet scene of a king—who is not otherwise known—between two women holding the standard offering utensils.

“Polygnotos was a rather current name in classical Athens. It is most often associated with Polygnotos of Thasos who painted large-scale wall paintings in Athens and Delphi that are described in ancient literary sources.” The Met

“In Classical Greek art, Medusa was progressively transformed into an attractive young woman. Simultaneously an aggressor and a victim, she became a tragic figure, as evidenced by Attic representations of her death. A red-figure pelike attributed to the painter Polygnotos preserves one of the earliest depictions of a beautiful Medusa (fig. 8). The Gorgon sleeps

peacefully on a hillside as Perseus approaches, sickle in hand, and grabs her by the hair. He looks away to avoid her deadly gaze, though it is disarmed by sleep. The goddess Athena stands next to him, looking on sternly. Quite unusual is the presence of a nimbus, or halo of rays, around Perseus’s head, now faint but still visible. Perseus is the only hero depicted with these rays, but rather than glorifying him, they probably allude to his katasterismos, or his ascension to the night sky upon his death and subsequent transformation into a constellation.14

“References to Medusa’s beauty can be traced as far back as early fifth-century b.c. poetry—Pindar, for instance, speaks of the “beautifulcheeked Medusa” (Pythian Ode [12.16)—and scholars have long surmised that a lost monumental wall painting was the inspiration for this and other similar contemporary depictions of the myth.15

“The act of beheading a beautiful sleeping maiden seems rather unheroic, however, and it is unclear whether the scene on the Polygnotos vase is intended to elicit sympathy for the monster or laughter at the hero.16

“In the late Classical period the trend toward humanization and feminization intensified while,

at the same time, the violence of Archaic representations of the beheading returned. On a redfigure pelike, Medusa, now wingless and nude from the waist up, and with an agonized expression on her face, gestures dramatically as she pleads for her life (fig. 9). Centuries

later, depictions of the episode, such as an eighteenth-century etching by Alexander Runciman (fig. 10), likewise attempted to provoke pity in the viewer for the monster’s impending demise.” “Dangerous Beauty: Medusa in Classical Art : The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2018/dangerous-beauty. Accessed 6 Sept. 2022.

1774

Alexander Runciman British, Scottish

“After the fourth century b.c., Medusa’s decapitation and the ensuing pursuit of Perseus by the Gorgons ceased to be illustrated, while subsequent episodes in the myth—such as the rescue of Andromeda, which predominates in Roman art—gained in popularity.17

“Gorgoneia were ubiquitous until the end of antiquity, appearing on temples, artisan work shops and kilns, private houses, furniture, utensils, drinking cups, and other vessels. They were

incorporated into fortification walls and gates, lined the edges of the roofs of temples and other buildings, adorned the coins of many Greek cities (fig. 11), were engraved on gems and cameos used as personal amulets, and ornamented shields, helmets, cuirasses, and greaves (armor that protects the shin). Their countenances, grisly and transfixing, were thought to have protective, defensive powers by intimidating the spectator and provoking fear in the enemy. This omnipresent and grotesque, almost comic visage may be explained as a bearable reflection of the terrifying alterity of death.18 Indeed, one contemporary writer has argued that the inspiration for Medusa’s visual representation was the bloated face of a recently dead and decomposing body.19

“Like the figure of the Medusa, the Gorgoneion underwent a transformation from grotesque to

beautiful, but since attractive faces cannot easily incite fear, artists portrayed Medusa’s head with wild, snake-infested hair; a pathetic, agonized expression; and other unnerving elements such as exposed teeth. This transition is apparent in a variety of media. It is vividly illustrated on a series of terracotta antefixes (roof tiles) from the Greek colonies in southern Italy dating from the early sixth to the early third century b.c. (fig. 12). An

imposing, grotesque Gorgoneion occupies almost

the entire surface of Achilles’ shield on a frag

–

mentary Attic terracotta relief (fig. 13), while a

beautiful version is emblazoned on the shield of a

terracotta warrior figurine (fig. 14). Two fine

Terracotta antefix (roof tile)

Fragment of a terracotta relief

ca. 600 B.C.

Greek, Attic

4th century BC

Horse and rider early

“The figurine, in the Kourion style, is handmade and solid. The rider’s face is mold-made, as is the device on the shield. The horse has a large head and a pronounced forelock between its ears. The rider has an elongated body and short legs.” The Met

Perseus Triumphant

1813

Domenico Marchetti Italian

Intermediary draughtsman Giovanni Tognolli Italian

After Antonio Canova Italian

Terracotta kylix: eye-cup (drinking cup)

Head of Medusa

1806–7

Studio of Antonio Canova Italian

‘On view in the Museum’s Carroll and Milton Petrie European Sculpture Court is the marble version of Perseus with the Head of Medusa (67.110.1) that Canova carved for Countess Valeria Tarnowska. He wrote that he was also shipping a plaster of the Medusa head, lest the marble one add too much weight to the statue’s outstretched arm. The countess could attach the lighter plaster to the arm instead, and, placing a lit candle inside the marble one, which is hollow, she could watch the eerie light effects. Like many other Neoclassical Medusa heads, Canova’s is based on the ancient marble mask the Rondanini Medusa (Glyptothek, Munich).

“The motif of the severed head of Medusa teeming with snakes became one of the most characteristic subjects for cameos. The image of the head perfectly suits the round field of a tondo. Artists were challenged to capture in the motif a perfect stasis between the macabre and the sublime. Generations versed in the classics knew that Perseus presented the head to the goddess Minerva and that it thenceforth embellished her breastplate. By implication, it served the wearer as a protective talisman, tacitly announcing the triumph of good over evil.” The Met

Terracotta kylix: eye-cup (drinking cup)

ca. 530 B.C.

Signed by Nikosthenes

Signed Interior, gorgoneion (Gorgon’s face)

Exterior, obverse, between eyes, Dionysos, the god of wine, with satyrs and maenads; reverse, between eyes, chariot

“Nikosthenes was the leading ceramic entrepreneur in Athens from about 530 B.C. to the end of the sixth century. Because he signed his name often, we know that he had a large shop and exported actively. Many of the largest preserved Attic vases were made for the Etruscan market.

Terracotta stand

ca. 520 B.C.

Greek, Attic

“A significant amount of Attic pottery was produced for the export to Eturia. Indigenous Etruscan shapes were reinterpreted in Athenian workshops; the Hellenized variants then sold to Etruscan patrons in the west and often buried in their tombs. The Etruscan prototypes generally exist in the sturdy black ware called bucchero. This pair of stands represents the phenomenon of adaptation with a shape unique in Attic vase-painting. They probably held floral or vegetal offerings.” The Met

Limestone funerary stele (shaft) surmounted by two sphinxes

last quarter of the 5th century B.C.

Cypriot

“Elegant sphinxes are positioned back-to-back with their heads turned so that they could be seen in three-quarters perspective. The calm beauty of the creature’s head, the form of the palmettes, and the egg and dart molding that decorates the base of the platform are typical of Greek art of the fifth century B.C.” The Met

Terracotta kantharos (drinking cup with high handles)

Terracotta Little Master cup

ca. 565–550 B.C.

Greek, Attic, black-figure,

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247100?&exhibitionId=%7ba5d24936-6862-4f74-89bd-a199111fdfd4%7d&oid=247100&pkgids=469&pg=0&rpp=20&pos=36&ft=*&offset=20#:~:text=The%20larger%20cup,of%20this%20tomb.

Bronze foot in the form of a sphinx

ca. 600 B.C.

Greek

“Between the eighth and sixth centuries B.C., elaborate bronze vessels were among the preeminent creations of Greek artists. This foot was probably one of three supporting an extremely large, shallow basin. Mythological creatures such as the sphinx here and the griffin (1972.118.54) nearby should be understood as guardian figures not simply decoration.” The Met

“The uppermost part of the greave, where it widens to cover the knee, is often decorated with a figural motif.

“The gorgoneion (Gorgon’s face) is particularly appropriate in view of its round shape and power to transfix the enemy

Exhibition Overview

Beginning in the fifth century B.C., Medusa—the snaky-haired Gorgon whose gaze turned men to stone—became increasingly anthropomorphic and feminine, undergoing a visual transformation from grotesque to beautiful. A similar shift in representations of other mythical female half-human beings—such as sphinxes, sirens, and the sea monster Scylla—took place at the same time. Featuring sixty artworks, primarily from The Met collection, this exhibition explores how the beautification of these terrifying figures manifested the idealizing humanism of Classical Greek art, and traces their enduring appeal in both Roman and later Western art.

The connection between beauty and horror, embodied above all in the figure of Medusa, outlived antiquity, fascinating and inspiring artists through the centuries. Medusa became the archetypical femme fatale, a conflation of femininity, erotic desire, violence, and death. Along with the beautiful Scylla, she foreshadows the conceit of the seductive but threatening female that emerges in the late nineteenth century in reaction to women’s empowerment.

President’s Note

“Medusa, the monstrous Gorgon of Greek mythology whose gaze turned beholders to stone, became increasingly anthropomorphic and feminine beginning in the fifth century b.c.

A similar transformation occurred in representations of other female half-human beings from

Greek myth, such as sphinxes, sirens, and the sea monster Scylla. Believed to have protective

powers, these mythical hybrid creatures were frequently employed on sepulchral monuments,

sacred architecture, military equipment, drinking vessels, and the luxury arts. Their metamorphosis was a consequence of the idealizing humanism of Greek art of the Classical period (480–323 b.c.), which understood beauty as the result of harmony and ideal proportions, a concept that influenced not only the representation of the human body but also that of mythological beings.

“The popularity of Medusa and other hybrid creatures from Greek myth has never waned, leading to their interpretation and adaptation in many other contexts. Among the most powerful and resonant in Western culture, their stories and images have inspired poets, artists, psychoanalysts, feminist critics, political theorists, and fashion designers. This Bulletin and the exhibition it accompanies explore the changing ways in which Medusa and other hybrid creatures were imagined and depicted from antiquity to the present day. Drawn primarily from The Met collection, the exhibition examines a wide range of works dating from thelate sixth century b.c. to the twentieth century, from ancient Greek armor, drinking cups, and funerary urns to Neoclassical cameos and contemporary fashion. Also featured is one of the earliest portrayals in Greek art of Medusa as a beautiful young woman.

“Dangerous Beauty: Medusa in Classical Art,” on view at The Met until January 6, 2019,

is organized by Kiki Karoglou, Associate Curator in the Department of Greek and Roman

Art, who is also the author of this Bulletin.”

Daniel H. Weiss

President and CEO

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Hi there, I hope you’re doing well. I’m reaching out because I believe you would be interested in a software called Jasper AI. It is a robotic writer powered by AI technology that can curate content material 5x quicker than an average human. With Jasper AI, you receive 100 original content with zero plagiarism flags that are accurately written. You also get pre-written templates on particular categories. Jasper AI writes SEO-friendly content material, which means all the content material that you get by utilizing Jasper AI is optimized and prepared to attract sales.You can try it out for free here: JasperAI. I’d really like to hear your thoughts once you have tried it out.